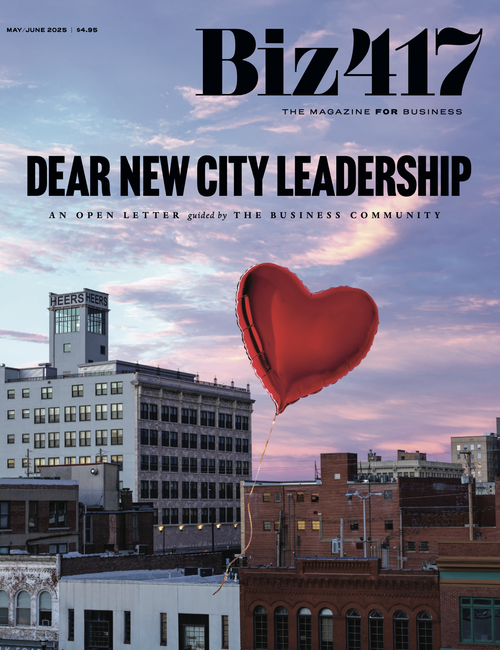

Strategy

Thank You For Firing Me

Meet 11 successful businesspeople who turned a stumbling block into a launching pad.

By Claire Porter | Photos By Brandon Alms

Nov 2015

Getting fired isn’t written into anyone’s career plan, but sometimes it takes falling down flat to position yourself for triumph. Meet 11 successful businesspeople who turned a stumbling block into a launching pad.

JUMP TO A STORY

Economic downturns and recessions put many workers out of jobs, but for Jack Stack, the downturn of the 1980s didn’t just affect him; it kicked thousands of his co-workers at International Harvester out of the factories and onto the streets.

At the time, Stack was plant manager of Springfield Renew Center, a division of International Harvester. He had started working in Illinois at International Harvester when he was 19. “I basically failed at everything else in my life, so I went and got a job at a manufacturing facility,” he says. “I started in the mailroom, and then I progressed through the organization.” He took advantage of tuition refund programs to go to college. His open-book strategies also helped him work his way up. “The more information I shared, the faster I got promoted,” he says. It worked so well that in 1978 he was promoted and transferred to Springfield to run the remanufacturing factory here.

Four years later the economy was singing a different tune, and International Harvester initiated mass layoffs and restructuring to stay afloat during the recession of the early 1980s. The layoffs were a nonstop topic of major headlines and newscasts, and Stack’s employees came to him worried about the stability of their careers. The factory was moved into a diversified group, which is when Stack says he knew they were on the chopping block. After months of being in a state of anxiety and fear, Stack proposed that he and the employees buy the company. “What alternative do we have?” Stack asks. “We either shut it down; or you live with a company that has no capital, which is bankrupt; or they sell it to somebody. Those were the three choices. We said to ourselves, if they’re going to sell it to somebody else, why not take a run at it?”

As Stack soon found, buying the factory was much easier said than done. After receiving Stack’s proposal, the International Harvester executives investigated the factory’s books, but shortly thereafter, Stack came across an ad posted in The Wall Street Journal that listed the factory for sale, dashing the hope he had built up after months of uncertainty. In October of 1982, Dresser Industries entered negotiations to purchase portions of International Harvester and began what Stack calls a weird, weird deal to purchase Springfield Renew Center. Originally, Dresser was only purchasing the construction equipment division, which excluded the remanufacturing factory; however, as one Dresser executive told him, the only reason they wanted the factory was because it was priced so low that if they were to liquidate, they would get their money back. “That couldn’t have been more of a slap in the face,” Stack says. Demoralized, he and his team acclimated to being able to work for a new company.

By this point, Stack had hit his breaking point. “I couldn’t face these people and tell them that we’ve gone from one frying pan into another frying pan,” he says. The nation’s unemployment rate was at 12 percent, and Stack had four children to support at home. Leaving the factory wasn’t an option. Just as Stack had resigned himself to working under Dresser, International Harvester broke off the deal. On December 15, they approached Stack and offered to sell him the facility. “I almost fell over,” he says.

Having a strong foundation of engaged employees is integral to Stack’s next career move: retirement. Through the next few years, Stack hopes to build a big enough balance sheet so that the next generation has the freedom to reinvent the company however they see fit. “We’re really, really making certain that the company can be a 100-year-old company,” he says. With his legacy in place, his rescued company thriving and his signature management style gaining traction, Stack is ready to slow down. As to how he’s leaving the working world, he plans to go out the same way he came in, with a bottle of Miller Light in his hand.

Because Stack’s background was in manufacturing and management, he had to learn how to run a business on the fly. “The best advice that I would give anybody to this day is, if you want to learn about business real fast, go out and borrow an enormous sum of money,” he says. “Seek capital, and when they tell you that you can’t have it, that’s when you start learning, and you begin to think like an investor.” For every rejection he got, Stack would sit down and figure out why he was turned down, then he would revise his business plan to address it. “Every time, I had to write a business plan for a different level of Dante’s circle of hell,” he says. Each bank, insurance company and capital investor that denied him—and there were more than 50 of them—provided an insight into which metrics and values mattered most.

Eventually Stack learned enough to get it right, and he secured the funding needed to purchase Springfield Renew Center, which he renamed Springfield ReManufacturing Corporation (SRC). Now in its 32nd year, SRC is what most would call a highly successful company. “One of our mottos here is we are creatively paranoid,” he says. “We don’t take success lightly.” In fact, it wasn’t until SRC’s 25th anniversary that Stack and his team were finally able to cast aside their initial paranoia as to whether their grand experiment would work and recognize the company’s success.

That achievement is ultimately due to Stack’s open-book-management style, which has always been a core component of Stack’s working strategy. Ever since he first started in the industry at 19, Stack has shared financial data with his co-workers, even when he wasn’t supposed to. Sharing information is the cornerstone of open-book management. Through sharing profits, creating bonus packages and offering stock options, companies are able to empower their employees to be more successful. “We’ve got this gap between the haves and have-nots because we don’t spend enough time teaching the have-nots how the haves made it,” Stack says. Demystifying those financial figures and educating employees on how their roles play into the company’s success encourages employees to think beyond simply doing their jobs and to reframe their work as a significant part of the overall mission.

If International Harvester hadn’t been going under, do you think you ever would have ended up starting your own business?

“No, but I probably would have gone through a lot of getting fired from one company to another because what you see is what you get. It’s very hard for me to keep quiet. I just got a funny feeling that I would have had a lot of jobs over a long period of time. I wouldn’t have been able to plant myself here and raise a family and grow up in a great neighborhood.”

The ringing of a doorbell and a simple sales pitch in the 1970s is all it took to get Jim Quesenberry started in his 36-year sales career. As a student at what was then Central Missouri State, Quesenberry took a summer job selling Bibles door to door to finance the remainder of his education. “I found that I could do it, and do it better than most, and I made more money than what most college kids are accustomed to,” Quesenberry says. After his summer epiphany, he switched his major to business administration. Right out of college, Quesenberry took a job with Xerox, launching him into the office equipment business. From Xerox, Quesenberry then worked for Savin Corporation before taking a position with Modern Business Systems, which became Ikon Office Solutions. There he was district sales manager, covering four branches in southwest Missouri and Arkansas.

The Stumble

Although Quesenberry felt he was performing well, he and his boss did not see eye to eye on how to run the business. “This is going to sound crazy, but on Friday the 13th, April of ʼ89, I got fired,” Quesenberry says. “When you are among the top performers, you don’t really anticipate something like that happening.”

Quesenberry capitalized on his five years of industry experience and got a job with another office equipment manager in the Midwest. His job consisted of working with independent dealers by helping them meet their sales quotas and by examining their sales methods. “What that affords you the opportunity to do is learn best-of practices,” Quesenberry says. He was able to dissect how certain companies became successful and what strategies they used to stay on top. After enough studying, “I felt like I could do it better,” he says.

Despite the learning experience it afforded him, the job wore on Quesenberry because of the amount of traveling it required. “I woke up one day in a Chicago high-rise hotel,” he says. “It was my daughter’s 4th birthday, and I had missed three out of her four birthdays because I was on the road. It just hit me: Never in my youth did I experience that.” With that realization in mind, Quesenberry resigned and decided to launch his own business. On September 3, 1993, Corporate Business Systems was born.

Bringing Business to Life

Through the years, Quesenberry built that confidence by hiring an exceptionally talented team with years of industry know-how. “My dad always said, ‘Don’t be afraid of hiring someone smarter than yourself.’ I think he knew that in my case that wouldn’t be that difficult, and that’s really been the key to Corporate Business Systems,” Quesenberry says. When he first founded the company, Quesenberry began hiring employees who had been in the industry for many years and could deliver the demanding results needed to grow a young company. “You’ve got to go after and bring on board people that are highly skilled, that are ambitious, that are growth-oriented, that are career-oriented, and I think if you can consistently hire above-average talent, as a business owner, you have every right to expect above-average results,” Quesenberry says.

Going in, the plan was to optimize the existing relationships Quesenberry had in the market. “I think everyone wants to help new entrepreneurs and new business ventures,” he says. “America was built on hard work and core ethics, and as a purchaser or business owner sees other people making the same leap of faith that they made, they like to be a part of it in whatever small way that they can.” His first products were supplied by a contact from his days at Savin, and his business partner was a former Xerox co-worker.

In the early days, the challenge was taking on customers. They struggled to prove their legitimacy until they were able to land a large account with Springfield Public Schools. “If you as a fledgling business can handle the requirements of a high-demanding customer, that should give other people confidence in your ability to handle their needs,” Quesenberry says.

Hitting His Stride

Quesenberry’s aggressive push toward growth early on paid off. Now, after 22 years in business, Corporate Business Systems has bought five companies, has locations in four cities and currently employs 78 associates. Through the purchase of related businesses, such as the IT company Aztec Computing, Corporate Business Systems has expanded its capabilities to cover the spectrum of technology-related office equipment and services.

Although the capabilities of the company have evolved, the prized culture that has attracted Corporate Business Systems’ talented staff has remained. “We do look at culture very, very heavily,” Quesenberry says. The company rarely experiences turnover and offers numerous incentives and bonding and training opportunities for the employees to create an environment employees—Quesenberry included—are excited to work in.

“I wouldn’t trade [this job for] anything in the world,” Quesenberry says. “It’s been a great, fun ride, and here I am still doing it. This is a fun industry. It’s one that’s built upon solutions.” It’s not often that such incredible success follows a moment of career collapse, but Quesenberry has made it happen. When asked if he would thank his former boss for firing him and for setting him on the path to Corporate Business Systems, Quesenberry noted that the two have kept in touch. About 12 years ago, Quesenberry sent his former boss an email. “He wouldn’t admit that he had made a mistake,” he says. “That’s what I was trying to get out of it. He wouldn’t admit to that, but he did congratulate me on the successes we’ve enjoyed. I thanked him once again, and I wished him well and said if he ever came to southwest Missouri, I’d buy him lunch.”

If you hadn’t been let go, do you think you would have ever ended up starting your own business?

“I’ve often asked myself that same question, and I don’t know to this day if I can properly answer it because I didn’t see it coming … As a matter of fact, me and my company president took a little road trip and spent the evening at Lake of the Ozarks in the home of my boss’s boss who approved my [boss’s firing] me. I did ask him, ‘What were you thinking? Why did you allow that to happen?’ because I would have probably still been there today.”

Gretchen Dexter has always said she didn’t know what she wanted to be when she grew up, so instead she took jobs that interested her. When catalog company Direct Retailing opened in Springfield, Dexter and her husband, Phil, jumped into middle management. Within the next few years, the company was sold several times and then went bankrupt. Dexter, her husband and Gary Cummings, the IT director, purchased the company’s two brands, Linda Anderson and The Music Stand, and launched Rockridge Group.

Biz 417: How did you go about acquiring the catalog brands from Concepts Direct?

Gretchen Dexter: We were just kind of left there to run [the company] until it was done. We decided, the three of us, to purchase the intellectual property in the bankruptcy case from the major secured creditor. We started working on that deal, but before that was finalized, the physical property was auctioned. We bought quite a bit of the inventory and some of the furniture.

Biz: What inspired you to start your own business as opposed to getting a job with an existing company?

GD: The main reason why I wanted to do this is I don’t have a college degree. There aren’t a lot of opportunities to do the kinds of things I was doing and enjoyed in Springfield. I knew I couldn’t get the job that I wanted, so I thought, “I’ll just make one.”

Biz: You and your husband jumped into this together. That’s a big risk for a household to take.

GD: It was pretty scary because this is, especially for Phil and me, this is it for us. We were both investing, we were both employed by the company that went bankrupt, we were both doing this as a full-time-plus job. It was scary, but I don't think you can be a successful business owner and not be an optimist.

Biz: Has the trajectory of the business differed from your initial plan?

GD: We opened in August of 2008 on Campbell St. in downtown Springfield in a little store called Ampersand. We operated out of there for three years. We were initially going to be web-only because mailing catalogs is very expensive. It didn’t take too long for us to figure out that we weren’t going to generate enough revenue to pay ourselves the salary that we were at least making at the old company. We started mailing catalogs again in 2009.

Biz: What have been the biggest challenges of starting Rockridge Group?

GD: We have the IT director, and we have the art person, and we have the marketing person, but we didn’t have an accounting person

starting out. That was and continues to be our biggest challenge. It’s intense because we have literally hundreds of vendors and dozens of shipments a week. We’ve grown to the point where I can’t keep up. There are a lot of things about having a business that are intimidating and discouraging to me, and it has a lot to do with making sure all your t’s are crossed and your i’s are dotted just right. It’s almost like you’re discouraged from being an entrepreneur because of the regulations.

Biz: What do you wish you had known when you first started Rockridge Group?

GD: If I could go back, I would

say you need to go into this not assuming that you’ll do it all yourself forever. Be more willing to delegate. Don’t be such a control freak.

If the company hadn’t gone under, do you think you ever would have started your own business?

“If the company had stayed solvent, if the atmosphere had stayed where it was, I can see where that would have been the last job I ever had. But with just about every job I’ve ever had, I’ve thought, ‘What if this was mine? How would I do it differently?’ I’ve always said I never knew what I wanted to be when I grew up, but I’ve realized that I did. I wanted to be a business owner.”

As Brad Erwin will attest, timing is everything. Sometimes through careful planning and sometimes by pure chance, the pieces of Erwin’s career fell into place over the course of 12 years, culminating in him launching the successful client-focused firm Paragon Architecture.

May 2003:

After proposing to his wife, Erwin gave his three weeks notice at his firm in Chicago and moved to Springfield without a job or any prospects. “Luckily I had a follow-up interview the second week I was down here, then by the third week, I was hired,” Erwin says. The job was as an architect-in-training at Creative Ink Architects.

2003 to 2009:

As the firm grew from seven associates to 20, Erwin’s role expanded as well to include IT, marketing, business development and HR duties.

October 9, 2009:

At the height of the economic downturn, Creative Ink was struggling to keep its head above water. To make it through, the company had to lay off all but four people.

December 2009:

Even at four employees the company was barely staying in business. The team set a series of target dates to reassess their standing, the last of which was mid-February 2010.

February 2010:

As projects continued to disappear, clients stopped paying and insurance skyrocketed. The team was faced with a tough choice. “We decided that the best thing for the five individuals that were left [four employees and the owner, Bob Stockdale] was to, as we say, ‘blow it up,’” Erwin says.

Blowing it up meant restructuring, reorganizing and firing all employees while the sole principal, Stockdale, carried the firm on alone. Meanwhile, Erwin worked on a recovery plan to re-employ those who had been laid off in October and February. Rehiring them was his only goal, and it meant starting a new firm from the ground up.

March To April 2010:

Two days a week, Erwin worked at Creative Ink to finalize the transition while also working on his own recovery plan. The time commitment of working 70-hour weeks during that transition was his biggest challenge. He struggled to devote enough time to the two businesses while still being around for his family.

May 2010:

Erwin credits Stockdale’s guidance for helping the new business, Paragon, gain its footing. A few joint venture projects between Paragon, Creative Ink and firm Buxton Kubik Dodd came together in May to put Paragon on stable ground.

June 10, 2010:

“We were back up to the four people that were fired in February,” Erwin says. The new Paragon set in motion a lot of the plans they had set up at Creative Ink. “We were able to take that strong base and accelerate faster,” he says. Their small group made them nimble and able to take on riskier projects. “There wasn’t any risk in doing something different because it was failure or this,” he says.

Today

Now the team is up to 11 people with offices in Springfield and Joplin. Paragon has set itself apart in the industry with its person-focused approach to architecture and its community emphasis. “Even if it failed within the first year and I was back somewhere else, there was so much personal and professional growth,” he says. “Going through that experience of leaving, ramping up and then trying to grow another entity has been awesome.”

If the firm hadn’t faced the downturn, do you think you ever would have ended up owning your own firm?

"No. We were on track. Everything that we’re doing here right now, that was the goal, but to do it under a different flag, to do it under different colors. If the downturn hadn’t happened, I don’t think Paragon would be here, especially not in this form.”

.jpg)

When Greg Horton first met Muriel Davenport, Carrie Gratton, Pam Thompson and Ronda Thompson of Oxford HealthCare, he immediately noticed what he calls their selfless servant hearts. So when the four women were let go at the home care company, Horton knew he had to help. “I remember when I visited with those ladies the first time, I was so struck by their selflessness and how in the middle of a very difficult time for them, they were more concerned about the other people that they cared for and cared about than they were about themselves,” Horton says. “That was what inspired me to offer to support them, whatever happened, without having a plan.” Little did any of them know that support would come in the form of a brand new company, Integrity Home Care.

Preparing for Change

Davenport, Gratton, Pam Thompson and Ronda Thompson started as caregivers and then worked their way up through Oxford’s organization. In 2000, the company implemented a range of quotas they expected the staff to meet regarding the number of patients in their care. At the same time, employees were asked to sign a non-compete agreement. “You couldn’t work anywhere [in the healthcare field] for two years in a 100-mile radius unless it was in a lower position,” Davenport says. “Well, I was barely making more than minimum wage, so I thought my future would be stalled. I can’t do that to my family.” The four were concerned about the stability of their careers if they couldn’t meet the company’s new quotas, so after researching other options, each decided not to sign the non-compete clause and was let go.

For Ronda Thompson, Pam Thompson, Gratton and Davenport, switching careers wasn’t an option. To them, healthcare was all they knew. Ronda Thompson had worked in the home care industry since graduating high school, Pam Thompson first got into the industry when she joined her daughter at Oxford, Gratton discovered her passion after caring for her mother who was battling cancer and Davenport made the switch to healthcare from daycare and had plans to become a nurse. All four had found their passions and weren’t ready to give them up after leaving Oxford.

A Serendipitous Moment

While the now former Oxford employees were determined to stay in their careers, Horton was doing just the opposite. He was working as a CPA for Whitlock, Selim & Keehn while also doing week-long mission trips in South America in his personal time. “I always felt like I accomplished more that was significant in those nine or 10 days serving others than the whole rest of the year put together,” Horton says. He remembers praying what he calls a dangerous prayer as he contemplated ways to lead a more fulfilling life. That prayer was asking for a career redirection.

As fate would have it, a nurse working in the healthcare consulting arm of Whitlock, Selim & Keehn knew some of the Oxford employees personally and learned they were looking for options while deciding whether to sign the non-compete agreement. Through him, Horton and the women met, a moment Horton knew was the solution to his prayer. “Without a great deal of forethought, I committed to help them if they got fired for standing up for what they believe in,” he says.

New Beginnings

As soon as the group was laid off, Horton quickly began setting the wheels in motion. “The fact that these ladies knew how to do their job was probably the thing I worried least about,” he says. “But getting the business organized without much of a head start or warning was probably the biggest challenge.” The combination of Horton’s background in business consulting with a specialization in healthcare significantly shortened the setup process. “There was no paycheck that was missed,” Pam Thompson says. Within 30 days of starting the process, Integrity Home Care was in business.

From that point forward, the momentum never slowed. “The growth experience was tremendous,” Horton says. “A lot of that was the reputation of these ladies. People sought them out, wanted to work for them and wanted to be cared for by them.” Davenport says that overcoming the challenge that most new businesses face of building a reputation was made easy by the established personal relationships she and her co-workers had built throughout their careers. In the initial years, former clients and co-workers would call Integrity and ask to work with them specifically, Ronda Thompson says, in part because of the way Horton and the company owners looked out for their employees. “They’re attracted to an organization that they believe will care for them in the same way that they care for others,” says Horton. This past summer, the Joplin branch celebrated a growth milestone by serving their 1,000th client; however, Davenport’s response to the triumph is indicative of the Integrity core values she embodies in her work: “It never feels like it’s that many clients, though. To me, they’re individuals. It’s one client. It’s one individual who has needs we can meet and help.”

This selfless drive to help others is what Horton says set the foundation for the company’s core values. “The source of it is love,” he says. “You have to love somebody in order to care for them that way. Seeing that in [the group’s] lives in a moment of crisis, which is when you see what people are really made of, they just embodied that. That had to be our core.” The company name also sets a daily reminder of the very reason Integrity is in business. “To act with integrity, to us, means doing the right thing even if it’s difficult, and even if no one else will know that you did,” Horton says.

Gratitude is not explicitly listed as Integrity’s core value, but all five employees live gratefully as if it were their mission. The former Oxford group is thankful for the experience they gained there. “They did what was right for them, and we did what was right for us and the principles that we valued,” Davenport says. As grateful as they are for their backgrounds, each is even more grateful for the opportunity to turn a dead end into a lifelong career in the field that they love.

If you hadn’t been let go at Oxford, did you ever imagine your career taking a turn like it did?

Pam Thompson: “Never. That was my passion, and I knew I was going to find it somewhere, I just didn’t know where.”

Ronda Thompson: “Never.”

Muriel Davenport: “Never. Never in my wildest dreams. I thought I was going to be a teacher!”

Throughout his entire career, Lynn Reeves has worked in the sporting industry at every level, from stocking shelves to running a business. What he didn’t realize as a teenager working the retail floor was that one day he’d own the company behind the products he was selling.

His first job as a teenager was working at the Montgomery Ward department store in the sporting department. He was then offered a position in a management training program at Service Merchandise where he soon became the sporting goods department manager. Eventually, Reeves was promoted to a fishing and tackle merchant position at their headquarters in Nashville. Springfield had always been home for Reeves and his wife, so when Johnny Morris called to offer Reeves a position at Bass Pro Shops, he jumped at the opportunity.

There, Reeves was fishing merchant, a job that entailed working with factories abroad to develop the Bass Pro brand of products. The relationships Reeves formed with the factory owners and the expertise he gained would prove to be valuable assets because 27 years after starting his job the country went into recession, the company went through a massive layoff, and Reeves’s position was eliminated. After working at Bass Pro for 27 years, Reeves says he could be bitter over losing his job. “It was a very frustrating time,” Reeves says. “But at the same time, we’re a very successful company, and I have to appreciate the opportunity that I had at Bass Pro.”

About two months after getting fired, Reeves began to talk to Casey Childre, owner of Lew’s, a brand of fishing rods and reels. Since Childre’s father, Lew, founded Lew Childre and Sons Inc. in 1949, the brand had been licensed twice and then sat dormant for several years. The Childre family was looking to revive the brand, and Reeves’s experience, industry connections and newfound availability made him the perfect candidate to do so. By December 1, 2009, Reeves had purchased Lew’s and opened for business. “Quite honestly, most of my friends in the industry thought I was crazy,” Reeves says. “The Lew’s brand, it had been off the market for so long, they didn’t feel it had any market appeal, and it was quite a risky venture.”

To Reeves, the risk was worth it because of his strong belief in the drive toward quality and innovation that stands at the core of the company’s values. “There are many reasons for our success, but the foundation of it is having a good product,” Reeves says. He notes that their high-quality products and the familiarity of the Lew’s name gave them a significant edge over other new brands entering the marketplace.

However, building a company from the ground up is rife with challenges, even if the company has 60 years to its name. To get the business running again, Reeves sought help from some of the many small business resources available in Springfield. He acquired funding from Liberty Bank’s SBA program and turned to the Missouri State Small Business and Technology Development Center for help writing his business plan. Thanks to Reeves’s connections from his time at Bass Pro, he also had a panel of experts to turn to for technical advice and assistance.

The advantages of Reeves’s time at Bass Pro didn’t stop at the industry connections. Because of the economic climate in 2009, many of Reeves’s coworkers had also been laid off and were out of work. “One of the exciting things that happened in that time frame was everyone who came to work for Lew’s had been unemployed,” Reeves says. “We were able to help a lot of families because there just weren’t a lot of jobs available.” To this day, six of those former Bass Pro employees still work at Lew’s. Another key player involved from the beginning is Reeves’s business partner, Gary Remensnyder, who also lost his job during the cutbacks. Remensnyder’s background was in sales and marketing, which complements Reeves’s product-sided expertise. “You’ll find out real quickly that one person can’t do it all,” Reeves says. “A team is so important.” With Remensnyder’s existing relationships with major customers, the initial staff’s decades of combined experience, and Reeves’s manufacturing connections, the Lew’s team was ready to hit the ground running.

Through all the successes, Reeves has always remembered the man who made it all possible. This summer, Lew’s moved to a brand new 58,000-square-foot facility. At the groundbreaking ceremony, Reeves took a moment to thank Johnny Morris for firing him because without the crucial experience he gained working at Bass Pro, he says he would have never been able to own a successful company like Lew’s.

Since founding in 2009, Lew’s has experienced steady growth. In fact, they have introduced more new items for 2016 than they had in their entire line in 2010. Even after six years of Lew’s success, this growth still surprises Reeves. “Who would have ever thought that I would have had this opportunity?” he asks. Because of this, Reeves emphasizes giving back to the community and to his company. Employees are part of a profit-sharing program, and outside of the company, Lew’s supports high school and college fishing programs and even provides fishing scholarships. Additionally, Lew’s developed the American Hero series, which donates fishing reels and rods to veterans organizations with an emphasis on the outdoors.

If your position hadn’t been eliminated, do you think you ever would have ended up owning a business?

“No, because I wouldn’t have taken the risk. To be able to do this, my wife and I had to assign all of our assets [for bank loans], which, at that time when the economy was so bad and the opportunity for failure was so great, was a huge risk. I probably wouldn’t have done that. These type of opportunities don’t come around very often, and I was very fortunate to be able to do this.”

For many, getting fired means gathering your years of experience and carrying on within that industry. For others, it means switching paths entirely. Jason Whorlow did just that when he went from supervisor of a factory to owner of a company that offers corporate, winery and wedding entertainment. With assistance from a staff of eight musicians, Whorlow delivers a one-of-a-kind mix of DJ, emcee, solo piano, dueling pianos and full-band music. Whorlow’s background in music began with classical piano lessons in high school, but it ended abruptly when he decided there weren’t viable careers available in the music industry.

Biz 417: after college, you took an eight-year hiatus from music. What prompted you to change career paths?

Jason Whorlow: I was working my way up in the factory building transmissions and hydrostatic pumps and motors. I got laid off, and I decided when they called me back after a couple months off that I wasn’t going to go back. I absolutely did not love what I was doing. I thought if I’m not doing anything for a career, I should do something worthwhile. I started working with individuals with disabilities. I felt like I was doing some good with myself, but didn’t think I could support my family on social work. [My wife, Karri,] got pregnant with Brianna, and that motivated me like I had never been before. I was driven to a point that I had never been to be successful with my music because I felt like that was where my passion was, and I wanted to go after that. I never really had any aspirations of starting my own company. I just wanted to play music.

Biz: What made you change your mind?

JW: I started playing at the piano bar a lot. I got my repertoire up to where it needed to be to be able to entertain on the weeknights. My wife is a court reporter and works during the day. Playing until 1 means I don’t get home until about 2, so I don’t go to bed until 3 or 3:30. Then getting up with the baby at 6:30 or 7—I don’t have the energy to get the most out of my time with her. My showmanship was where it needs to be, I can pay attention to a crowd, I can read a crowd, and I can make a good show, but I need enough sleep, and I don’t want to just play to a drunken bar crowd all the time. That drove me to say, “What else could I do with this?”

Biz: What was the most challenging part about starting this business?

JW: The uncertainty and not knowing if I was going to be able to have the income to pay the bills because there’s nothing on the calendar.

Biz: At what point did you overcome that uncertainty?

JW: It was last summer when I started booking events into this year. Last year was my first year to do weddings as an entertainment company, and I ended up booking 17 weddings. That was just the start, but I obviously wanted to do more than that. My goal was to at least double that for next year. As of right now I have 37 weddings on the books for my second year.

Biz: did your Position at the factory prepare you to run your own company?

JW: I feel like that was integral because I took a lot of the Six Sigma Projects, the management classes that the company would offer to make us better. Working with eccentric musicians tends to bring the opportunity to manage often. I’ve gotten so much better I think because of working at the factory and managing those 18 employees that were under me.

Biz: What Strategies have contributed to your success?

JW: Word of mouth has been pivotal. When a venue experiences my company, they see what I have to offer, they see the value and versatile showmanship, and they convey to the client the importance of hiring my company. When that venue and that company that’s already solidified in the community will put their stamp of approval on me and say, ‘You’ve got to have this guy,’ that puts those clients’ minds at ease. When I see a beautiful venue, and they’re promoting me, and I see how well they handle their events I will tell everybody this venue is one of the best. I think that’s very important for local businesses to support each other, recommend each other, and refer each other.

If you hadn’t been laid off, do you think you ever would have ended up where you are now?

“No, probably not. Probably because I would have just settled because it was convenient. At the time I didn’t have a family, so I lacked the self-motivation to aspire for a more prominent role in the community.”

Resource Guide

Get Back On Your Feet

Head over to the Missouri Career Center for help filing for unemployment or to search for a new job.

Missouri Career Center–Ozark Region

Visit labor.mo.gov/unemployed-workers to file for unemployment online.