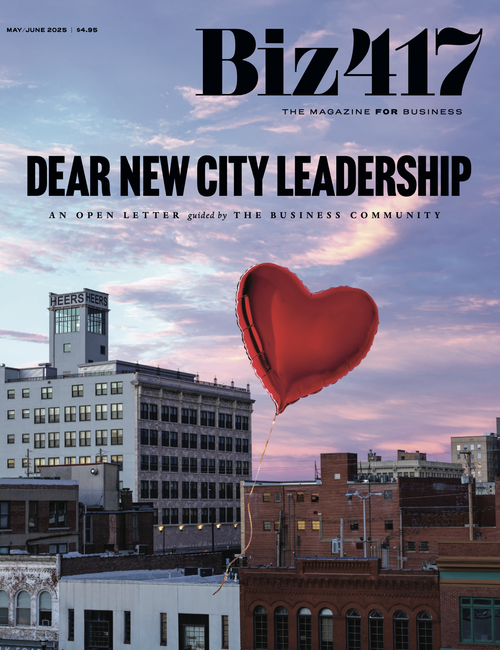

John Quentin Hammons, born February 24, 1919, pictured with his sister Wrenna Quentilla Hammons, often lied about his birthday.

Entrepreneur

The Curious Legacy of John Q. Hammons

What’s next for Hammons Tower, Hammons Field and other Springfield attractions that bear the name of our city’s greatest real estate investor?

By Ettie Berneking

Jan 2019

The first thing you should know about John Q. Hammons is he lied.

Well, sort of. His name was not John, and his birthday did not fall on Presidents Day. Hammons—known better as John Q.—was actually born James Quentin Hammons. And his birthday, despite what he told people, was February 24. For nearly 24 years, John Q.’s executive assistant, Jan Robbins, watched her boss fib about his name, age and birthday. She watched him send dozens of cards out on Mother’s Day and even more poinsettias on Christmas. She got calls when he ran through stop signs, and she brought him his one cup of coffee each day. She watched as Hammons’ name popped up not only in Springfield but around the country.

By the time he died on May 26, 2013, at the age of 94, Hammons had built 210 hotels in 40 states and was responsible for some of Springfield’s best-known buildings and cultural attractions including Hammons Tower, Highland Springs, Hammons Field, University Plaza and Convention Center, Juanita K. Hammons Hall for the Performing Arts and the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame. After his death, the Hammons legacy began to change as lawsuits and bankruptcy filings threatened to wipe his name from the very town he helped build. But would Hammons have cared? Robbins is not sure. “I don’t think he’d like it, but then there’s this side of me that’s not sure he’d really care,” she says.

John and Juanita, who he called Mrs. Hammons, were married for 64 years.

Becoming John Q.

During the prime of his career, around 1987, John Q.’s estimated wealth was $300 million. He was listed in Forbes magazine’s list of the 400 richest people in the United States. But John Q. was not born wealthy. There were no silver spoons, no trust funds. Instead, there were dairy cows and debt. John Q.—who was still known as James back then—was born in Fairview, Missouri, in 1919. His family owned and operated a dairy farm until the Great Depression tightened its grip, and the family lost the farm. The effect the Depression had on his family left a scar on John that he rarely talked about. But in his biography, They Call Him John Q. A Hotel Legend, by Susan M. Drake, John remembered watching his mom go to work in a local tomato factory and become the family breadwinner. “She was not in good health,” he said. “That really made an impression on me… I swore I would never be poor.”

Despite that promise to himself, poverty knocked at John Q.’s door for the first quarter of his life. His first job teaching science, history and physical education at Cassville Junior High brought in just $40 a month. His first business venture—mortarless bricks—went bust after two years, and John Q. lost $60,000. “I got down on my hands and knees to about six or seven big creditors,” he is quoted saying in his biography. He asked his creditors to give him three years to pay them back. It was that or declare bankruptcy, in which case they wouldn’t see a penny. The creditors agreed, and John Q. said he paid them back a year early. “I didn’t have a failure,” he said. “But I didn’t succeed.”

As John Q. told it, his first success came when he married Juanita K. Baxter in 1949. For the entirety of their 64-year marriage, John Q. referred to Juanita as Mrs. Hammons, and even in their early days, he warned Mrs. Hammons that business would be at the center of his life. “I didn’t have anything,” he wrote. “But I told her that I was going to be successful in business, and business was going to be part of everything I do.”

“I told her that I was going to be successful in business, and business was going to be part of everything I do.”— John Q. Hammons

To dig his way out from under the debt he had accumulated from the brick business, John Q. set his sights on rental housing. World War II had just ended, and veterans were returning home to find few housing options available to them. The market had a need, and John Q. had a vision that would fill it. He just didn’t have any money. According to his biography, the first property John Q. developed was Village Gardens No. 1. The development was built in 1949 in Springfield and was owned by Dan Savage Sr. and Herschel E. Bennet.

For his second housing project, John Q. sought the financial backing of J.V. Cloud, who believed in John Q.’s vision and promise of returns. The plan worked. “It made $200,000,” John Q. wrote. “I got half, and he got half. And later we sold it, and we got another $200,000.” Unlike his mortarless bricks, property development was working, so John Q. started following the money in town, which in the ’50s was headed south. According to his biography, John Q. started investing in land. By the time he was 38, he had accumulated five farms on the southern edge of Springfield. To develop that land, he teamed up with Lee McLean. “When we quit buying farms, we had nine in total,” McLean says. With roughly 1,000 acres to work with, McLean and John Q. began developing Southern Hills. “He worked hard and long hours,” McLean says. “That’s what it takes. You don’t have to have above average intelligence.”

By the late ’50s, John Q. teamed up with mechanical contractor Roy Winegardner. With vision, capital and plenty of bravado to propel them forward, the two started making moves to enter the hotel industry. Swankier hotels at the time like Holiday Inn were taking up a larger chunk of the market, and John Q. and Winegardner wanted a piece of that pie. They approached Charles Kemmons Wilson, the founder of Holiday Inn, and asked about buying into the franchise. As the story goes, Wilson gave John Q. and Winegardner 90 days to find 10 locations for their hotels. “Each one was $10,000,” says Debra Shantz Hart, previous senior vice president and general counsel at John Q. Hammons Hotels. “So Hammons and Roy did it. They optioned 10 pieces of property, and they say the rest is history.”

Winegardner and Hammons eventually opened 67 Holiday Inn hotels. Then in 1969, John Q. founded John Q. Hammons Hotels as a 50th birthday present to himself. John Q. and Winegardner remained partners, but the new company gave John Q. freedom to follow his intuition without partners taking the wheel. According to his biography, four years later, John Q. had 35 hotels under his belt and piles of paperwork around him.

Oh Henry!

"He was a hoarder,” Robbins says. Robbins joined John Q. as his executive assistant in 1981 when the burgeoning mogul still worked out of a one-story building on South Glenstone Avenue. “I’ll tell you exactly how I landed the job,” she says. “We had mutual acquaintances, and I had worked for law firms as a legal secretary and had a lot of real estate background. Whenever he invited me and my former husband to ballgames, he and I would talk real estate.” Her background and business prowess earned Robbins the title of John Q.’s “half-assed attorney.”

The first week she was hired, John Q. was out of town on business. Robbins—who wasn’t afraid to take on her boss—took one look around the cluttered office and decided to make the most of John Q.’s absence. “There was crap everywhere, so I cleaned it out,” she says. When John Q. returned to a neatly organized office, Robbins says he nearly had a stroke. “I did that twice in the 24 years I was there, and he wanted to fire me both times.” It was a threat that fell on deaf ears. “I said no problem,” Robbins says. “Knock yourself out.”

As days passed, the piles reappeared, and Robbins stopped giving John Q. original documents. He’d stuff blueprints of new projects in every available drawer and cabinet, and his imposing wooden conference table in the middle of his office was so cluttered only one lone island of tabletop was left, and it’s where John Q. worked each day.

Much of the legacy—and legend—of John Q. centers around his almost manic work ethic. If he slept, it wasn’t much. He could be a taskmaster and would call partners to demand numbers and details at a moment’s notice. If you didn’t know the answer, you didn’t dare guess. Bill Killian, owner of Killian Construction Co., worked with John Q. as a contractor for more than 25 years, and the two were partners on a private jet. Killian was John Q.’s contractor on more than 35 projects including Chateau on the Lake, the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame, Hammons Field, Hammons School of Architecture at Drury University and Highland Springs Country Club. “I learned early on that he demanded and expected people to be up-to-speed on projects,” Killian says. “If you didn’t know something, you’d better tell him that. But if you didn’t know, you’d better find out and get back to him.”

Few had the clout to say no to John Q., but Robbins could. “We teased a lot,” she says. “He had a nickname for me, and I had a nickname for him. One day he was doing business with one of his banker friends. They were of different political parties and would rant and rave about interest rates. I had a candy bar, it was an Oh Henry! bar, and I had heard 10 minutes of this crap. And finally I just held it up to him, and he just cracked up. So anytime I needed him to cut to the chase and stop being so full of himself, I’d say ‘Henry!’”

Not long after the Oh Henry! moment, Robbins got her own nickname when she overheard John Q. and one of his business partners talking about how they should hire a beautiful woman named Sally who happened to walk by them during their lunch meeting. “They were going on about how they needed to hire Sally,” Robbins remembers. “I’d heard enough of it. I said, ‘Good God. We don’t need someone else walking around here who looks pretty, we need somebody who can type!’” From that moment on, Robbins was Sally and John Q. was Henry. “When he signed his book to me, he put to Sally, love Henry,” Robbins says. “It was our deal, and it only belonged to us.”

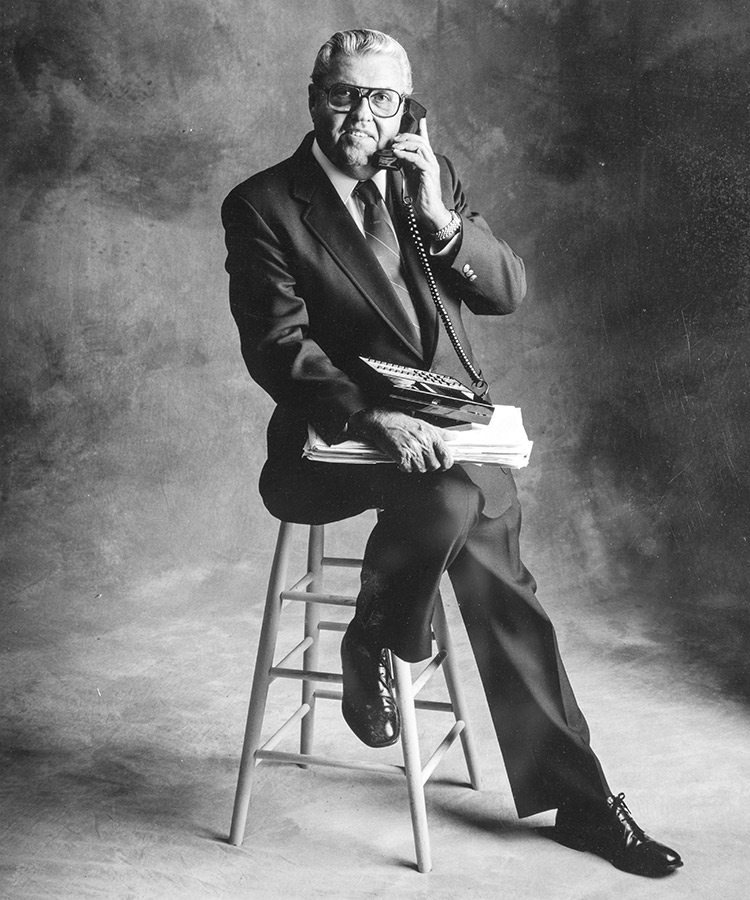

The Empire

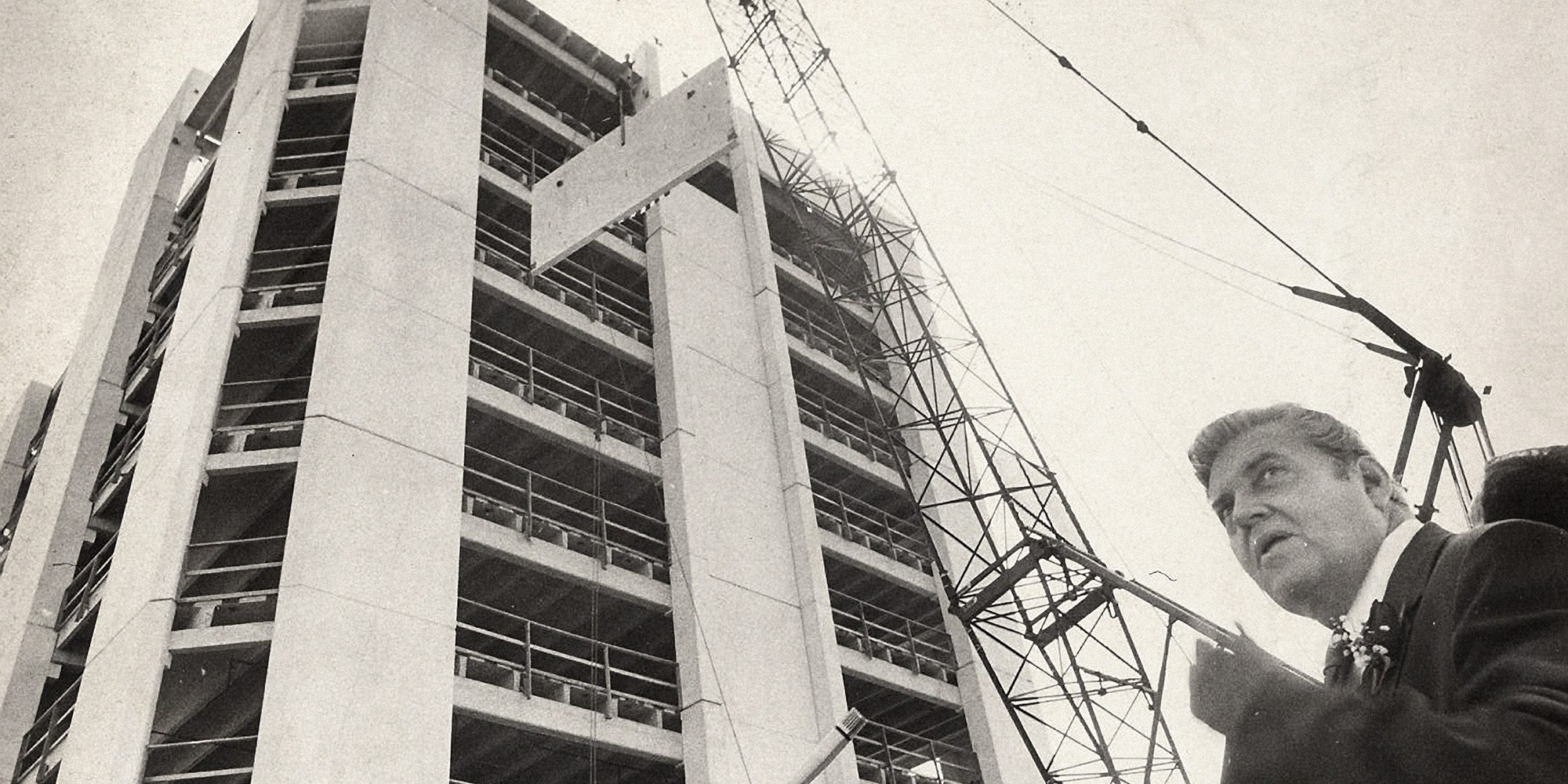

John Q. moved the business to the top three floors of the John Q. Hammons Office Building around 1983, and by the end of his career, he could look out over one slice of his empire through the wall of windows that lined the northwest side of his office. From his bird’s-eye view, he could see Hammons Field, the John Q. Hammons Enterprise Center—home to the Springfield Area Chamber of Commerce building—University Plaza Hotel and Convention Center, Hammons Tower and Juanita K. Hammons Hall for the Performing Arts. By the early 1980s, Hammons was doing business on both coasts, and with a growing business and increasing name recognition, John Q. showed no signs of slowing down. His workday started early and ended late. “He loved getting up early,” Robbins remembers. “He was usually in by 7:30 a.m. wondering where everybody was.” Robbins would bring him his cup of coffee—black, and just one cup a day—and John Q. would pick up the phone and not put it down until the end of the day. Calls to the East Coast were first, because surely someone was awake over there. By the time his call log reached the West Coast, the day had long since ended in the Midwest, but John Q. was known to talk all night. He was also known to take every single phone call that came through to his office. It didn’t matter if he was already in a meeting. You would just have to wait for him to get off the phone.

Shantz Hart especially felt this. “One day I got to his office at 9 a.m. and sat there till 11:30 because he was on the phone,” she says. “He said, ‘Maybe you should put a desk in here’... He took every call on speakerphone. It didn’t matter who he was talking to.”

When John Q. hired Shantz Hart in 1995, she says he referred to the job as chief nitpicker. He also lied about his birthday. “He said to me, ‘Today’s my birthday. I’m 75,’” Shantz Hart says. “Well someone else called, and he told that person a different age.” When Shantz Hart finally emerged from John Q.’s office, she stopped at Robbins’ desk and asked what his age really was. Turned out, it wasn’t just his age he was fibbing about. It wasn’t even his birthday. “You really can’t make it up,” Shantz Hart says, reflecting back on John Q.’s fibs.

John Q. had lots of quirks. On Mother’s Day, he’d send cards to dozens of wives and mothers he admired. “When people asked why I was buying so many Mother’s Day cards, I’d just say, ‘Well, he doesn’t know which is his mom,’” Robbins jokes. On Christmas, poinsettias found their way to employees and friends. And in each of his hotel rooms, Hammons placed directories of his properties. “He’d put them next to the Gideon Bible,” Shantz Hart remembers. “He loved mini-directories. They were all about him and his properties. He was convinced that people were staying at his hotels, and they were seeking them out.”

For his friends, Hammons had small collector’s cards made up and printed featuring different expressions he particularly liked or found amusing. Shantz Hart remembers receiving one that read, “A dollar repaid is a dollar lost forever.” It might have just been a saying at the time, but John Q. saw some truth in it. “He always said a contract was meant to be broken,” Shantz Hart says. As much as he hated poverty, he wasn’t scared of debt. “In fact, he liked debt,” she says. “He liked to do things on other people’s money.”

Staying highly leveraged was part of John Q.’s MO. Instead of working on one or two hotel projects and tying up a few million dollars at a time, he would work on a handful. At one point, Shantz Hart remembers working on close to 12 projects at once. “These were $65-million deals,” she says. But big budgets didn’t always mean big markets. John Q.’s sweet spot was a secondary market with a robust highway system nearby. Throw in a state capital and a college campus, and you’d struck gold.

Location was everything for John Q., and markets like Dallas; Frisco, Texas; Little Rock, Arkansas; Tulsa, Oklahoma; and Springfield gave him the chance to fill a niche in these growing communities. Once a city was picked out, John Q. would draw maps of the highway system to understand where traffic was headed. To get a better lay of the land, he would charter helicopters and planes to fly him over the area at night. Once they spotted large clusters of lights, he’d drop a pin in his maps. When John Q. began developing Chateau on the Lake, Killian served as the contractor, and Killian chartered a helicopter that took them to the top of the hill where the hotel stands today. The goal: See what the views would be like.

If there was one thing he avoided, it was older hotels. “He would never buy an existing hotel,” Shantz Hart says. If someone suggested revamping an already existing hotel, John Q. had a quote ready. “Grandma does not win in Atlantic City.” He also didn’t always follow the rules. In Hammons’ biography, David Sullivan, a Holiday Inn veteran who used to handle franchise requests for the hotel chain, remembers getting applications from John Q. “We had a long process where a potential owner would make an application, and then we’d study it and take it to a committee for approval… Well we’d get these applications from John Q., and we’d start the process, and when we’d call John Q. he’d say, ‘Don’t worry about it. The hotel’s already been built. In fact, it’s opening next week.’”

The Prayer Meeting in the Sky

For the business titan, athletics were his release. John Q. played basketball throughout high school and college and worked as a basketball coach during his early years teaching. His love of sports was one of his few interests outside of development. And Bill Rowe—MSU Athletic Director from 1982 through 2009—was along for the ride. “He always said, ‘If you get tickets someplace, remember I have the airplane.’” For years, Rowe and John Q. headed to Arizona and Florida to watch spring training. They attended final four basketball games and were at the World Series in 2011 when the St. Louis Cardinals clinched their 11th World Series win in the 11th inning of game seven.

It was Rowe who first approached John Q. about helping get the Missouri State Bears baseball team a new stadium. The Bears had been playing in city parks since the team first took the field in 1964, and building a new stadium excited John Q. But it wasn’t just building a permanent home for the Bears that had him amped up. He wanted to own a minor league team and bring them to Springfield. Eventually Rowe got ahold of plans for a new stadium Baylor University was building in Waco, Texas. With plans in place, it was time to pick a location for the stadium, and John Q. knew just where to put it.

The same day Shantz Hart interviewed for the position of chief nitpicker with John Q., her future boss took her to the window of his ninth-floor office and pointed at a pink motel in the distance. “He said, ‘Do you see this? I’m going to put a ballpark there,’” she says. “I realized later that this was the same guy who told me he was three different ages.”

But this time, John Q. wasn’t fibbing. He wanted a ballpark for MSU, and he knew which minor league team should be the main tenants—the Cardinals Double-A team. There was just one problem. John Q. also owned two gaming operations, including one casino in Reno and a gaming boat in Illinois. “Turns out you can’t own a sports team if you also own a gaming operation,” Shantz Hart says. John Q. could own the building but not the team. Shantz Hart was at the meeting when John Q. met with a family willing to foot the bill and take ownership of the Springfield Cardinals. The family had made its money with Ray Kroc and McDonalds and already owned a team in Tennessee, but the meeting was a disaster. “John Q. was very rude,” Shantz Hart remembers. “He did not give them the time of day. It was one of the only times I was really embarrassed.” Stumbling over her apology as the family was ushered out, Shantz Hart was caught off guard when the family smiled and said it was okay, and that God would use John Q. to do good things whether he knew it or not. “They had such a positive attitude,” Shantz Hart says. “He enabled people to do good things he might not have ever done, and that really struck me.”

“He enabled people to do good things he might not have ever done, and that really struck me.”— Debra Shantz Hart, Principal, Housing Plus LLC

With one deal down and out, John Q. headed to St. Louis with his architects and contractor Bill Killian to meet with the Cardinals and watch the redbirds play that same day. At the end of the meeting, John Q. stood up and shook hands. “They told him if he built the stadium he was showing them, they would try to move the Cardinals franchise to Springfield,” Killian says. Just like that, things were looking up, so before the game ended, John Q., Killian and Jerald Andrews, the president and executive director of the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame, boarded Killian’s private jet, and took off to Springfield. The hour-long flight has been seared in that group’s memory ever since.

“I could tell we weren’t as high as we usually were,” Andrews says. “The pilots were flipping through this manual, which was kind of strange, and then the pilot got up and came back and looked at Bill. He said, ‘We have all kinds of trouble up here. The hydraulics have gone out.’” The wheels were down, but the plane no longer had breaks, so they couldn’t stop the jet. As calmly as they could, the pilots explained they were going to attempt an emergency landing in Springfield. The plane would come from the south in a very steep decline and touch ground as quickly as possible to use every foot of the runway available. The only braking system they had was the emergency brake, which used a chemical release to lock the wheels. If they engaged the emergency brake for too long, the chemical would get used up before the plane could stop.

“They said if we pass the fire trucks you’ll know we won’t stop, and you need to get your heads down,” Andrews says. When the plane hit the runway, it was hard enough to make the oxygen masks come down. Each time the emergency brake was deployed, the wheels would lock up and screech against the asphalt. When one of the tires blew out, the plane started fishtailing. “The fire truck lights were right upon us,” Andrews says, “but before we went off the runway and into the dirt, we stopped.” Once off the plane, Andrew says the group was only 20 or 30 feet away from the jet when he heard John Q. turn to Killian and say, “Buy a new one.”

When Hammons Field finally opened in 2004, the MSU Bears were given their own locker room and batting cages, and in 2005 the Springfield Cardinals Minor League baseball team relocated to Springfield. Rowe says more than 9,000 people crammed into the stadium for the Bears’ opening game against Southern Illinois University. “They were on the berm and on the grass, and all 350 members of the marching band were on the field,” he says. John Q. threw out the first pitch, and Bill Rowe was on the receiving end behind home plate. He still considers that moment one of the greatest thrills in his life.

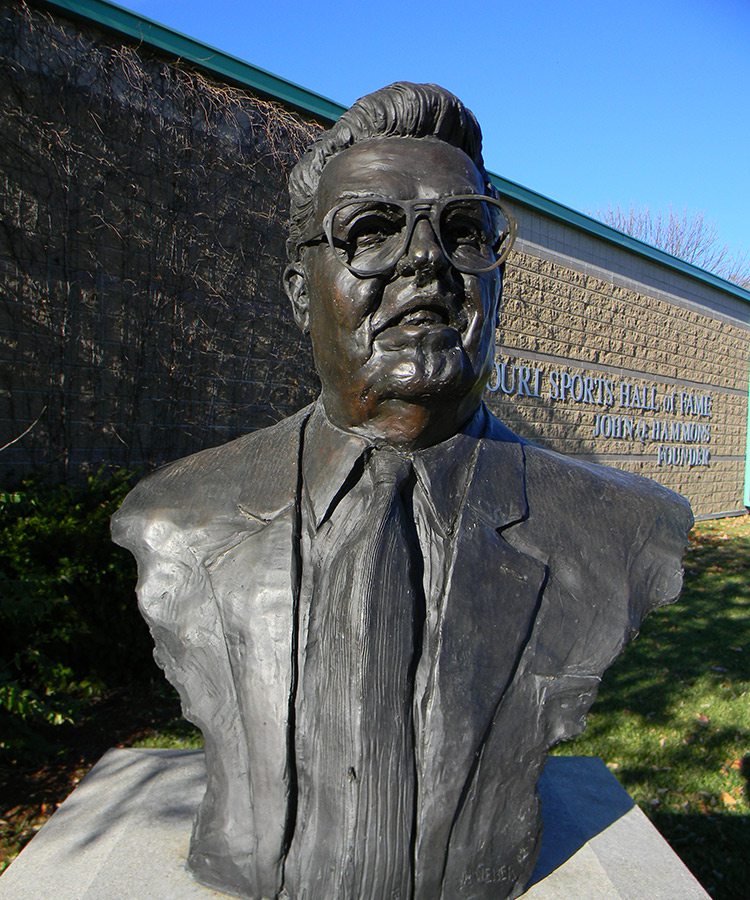

There is a bust of John Q. Hammons at the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame.

John Q. enlisted Jerald Andrews to make the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame a success. He is now president and executive director.

A Near Miss

If Hammons Field was a home run for John Q., then the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame was just one swing away from striking out. Before opening its doors in 1994, the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame was little more than a collection of plaques tacked to the walls of a conference room in Jefferson City. When John Q. was approached about developing an actual building for the Hall of Fame, St. Louis, Columbia, Kansas City, Joplin, Cape Girardeau and Springfield clamored for the opportunity. For John Q., it was a pretty easy decision. He already owned land in Springfield at the entrance of Highland Springs Country Club, and it checked all of his boxes: great highway system, state college, emerging market and name recognition. But operating the Hall of Fame wasn’t as easy as John Q. had planned.

“To be candid, he’d built it with the idea that admissions would carry it,” Andrews says. “That didn’t happen. Admission doesn’t carry Cooperstown or any national hall of fame.” John Q. hired Andrews in 1995 to manage the Hall of Fame. “The very first time I met him, he asked me to meet him at the University Plaza restaurant,” Andrews says. “I walked in and introduced myself. He was going over hotel plans, looked up at me and shook my hand. He said, ‘You and I are going to make a deal.’” It would be the first of many deals between Andrews and John Q. The second was figuring out how to bring the Hall of Fame back into the black. Andrews had his work cut out for him. Since opening in 1994, the Hall of Fame was losing money every month. It wasn’t a small cut. This was a gash. “[John Q.] was underwriting that loss for about $10,000 to $12,000 a month,” Andrews says. The Hall of Fame was bleeding out, and John Q. expected Andrews to patch the wound.

When Andrews showed up, only two volunteers were keeping the lights on, and not all of the lights even worked. That first day, Andrews bought 66 light bulbs at Lowes. The second day, he mowed the lawn. The following January, Andrews sold tickets to the Hall of Fame’s annual enshrinement event. “It grossed $60,000,” he says. After that, Andrews launched a series of ticketed events from luncheons with guest speakers and golf tournaments to off-site enshrinement galas and even a sporting clay shoot. When finances got tight, John Q. was there. He loaned the Hall of Fame $10,000 one time so Andrews could finish payroll. “We paid him back three days later,” Andrews says. Over time, the beefed-up events calendar worked, and the Hall of Fame was covering all of its expenses and had room in the budget to hire seven other full-time staffers.

Everything was looking up. The budget was under control, events were well-attended, and John Q. had promised publicly to endow the Hall of Fame building and the land it was developed on to the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame Foundation. But after John Q. died and John Q. Hammons Hotels & Resorts declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy, in June 2016 the future of the Hall of Fame and many buildings featuring the Hammons name was suddenly much less secure.

News outlets were alarmed by the sudden bankruptcy announcement, but those within John Q.’s inner circle had seen this coming for some time. It wasn’t the bankruptcy they could predict; it was a subtler shift in the way John Q. was doing business. As banking regulations changed in the ’90s, John Q. found it harder to secure multimillion-dollar loans from banks. “Lenders wanted more equity in deals,” Shantz Hart says. “It’s not that you don’t have money, but your equity is all tied up in other projects. John Q. was always highly leveraged.”

To open the taps again, John Q. had to do what seemed unimaginable for a man who hated to lose control: He took the hotel side of his company public. In 1994, JQH became publicly traded stock on Wall Street, and a board was assembled to hold John Q. accountable to his shareholders. Robbins took minutes during board meetings and remembers the ordeal as “gut-wrenching” for John Q. As his board started telling him no, John Q. looked for other injections of capital around 2002 and connected with Jonathan Eilian at JD Holdings. Eilian would supply the funds John Q. needed to take his company private again and would extend the developer a line of credit he could pull from for future projects. In exchange, JD Holdings took control of the 47 hotels in Hammons’ publicly traded company and got first right of refusal on all of John Q.’s future projects that pulled from JD Holdings’ line of credit. Once the deal was agreed upon, John Q. Hammons Hotels & Resorts went private again in 2005.

For Robbins and Shantz Hart, things started to change. “It changed who he listened to,” Robbins says. “He brought in more yes men. There were still those of us who spoke truth to power, but it became less and less important to him.” Robbins eventually left on January 20, 2005, and now serves as executive director of GYN Cancer Alliance. Shantz Hart followed in February 2008 and now develops affordable housing at Housing Plus, LLC. Earlier in 2007, John Q. had a heart procedure done at the Cleveland Clinic. As his biography recounts, John Q.’s heart had been a concern for some time. He’d had a heart attack in 1960 when he was 41 years old. It was a surprise but didn’t keep him down for long. This time was different. John Q. was 89 years old.

John Q. never retired, but he didn’t return to the office after his heart procedure. Most of his remaining years were spent in his penthouse at the Mansion at Elfindale. And for a reason still largely unknown, many friends found themselves barred from seeing him. What happened is still unclear, and few will talk about the details on the record. But friends including Bill Rowe and others had to hire lawyers to obtain the right to visit John Q. at Elfindale.

Then on May 26, 2013, John Q. Hammons died at the age of 94. He and Juanita had no children, so there were no heirs to take the torch.

Winds of Change

Three years later, John Q. Hammons Hotels & Resorts declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in June 2016. To really understand the motivation behind the bankruptcy, you’d have to ask Chief Executive Officer Jacqueline Dowdy—who declined to be interviewed for this piece. In an article in the Kansas City Star, Dowdy said the “company was financially stable and able to pay its bills.” The move was widely seen as a way to prevent JD Holdings from taking control of the rest of the Hammons properties. The way Shantz Hart saw things, “The bankruptcy didn’t need to happen. It was a Hail Mary attempt to avoid JD Holdings from exercising their right of first refusal.” The deal Hammons and JD Holdings originally made did not include John Q.’s private assets, including Hammons Field, Hammons Tower, Hammons Building, the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame or Highland Springs Country Club. But once the Hammons trust declared bankruptcy, all assets were on the table.

It also meant Missouri State University stopped receiving payments on properties John Q. had committed funds toward, including JQH Arena. When John Q. proposed building a new basketball arena for the MSU Bears, he agreed to provide a $5 million upfront gift, as well as payments for principal and interest on $20 million. To date, that is the largest single-donor gift MSU has ever received. JQH Arena opened in 2008 and cost $67 million to complete. The university agreed to pay 52.46 percent of that, and John Q. agreed to have the Hammons Trust cover the remaining 47.54 percent. When the company declared bankruptcy, Hammons still owed $22 million in principal. In May 2018, the university was notified that it would no longer receive payments. Mr. Hammons was still the largest donor on campus. His name is on a handful of fountains and four buildings, including Hammons Student Center, Hammons House residence hall and Juanita K. Hammons Hall for the Performing Arts. Those buildings were paid in full and weren’t involved in the bankruptcy. But Hammons still owed millions for the arena.

Changing Hands

The latest on who now owns some of Hammons' most iconic Springfield buildings.

The Tower Club

After the bankruptcy settlement, JD Holdings took ownership of The Hammons Building and The Tower Club located on floors 21 and 22 of Hammons Tower. Since switching owners, the club underwent several renovations and reopened as a public venue in November 2017. The once-private dining club now operates as an event venue.

Highland Springs Country Club

Early in his career, John Q. set his sights on purchasing land on the south side of Springfield. The property was eventually turned into Highland Springs Country Club. The club and golf course that John Q. developed is now owned by JD Holdings and operated by Atrium Hospitality.

John and Juanita’s Home in Southern Hills

John and Juanita’s 4,942-square-foot Southern Hills home was listed for $1 million in May 2018 by Murney Associates Realtors agent Sherrie Loveland. Real estate investor Kim Kaufman and his wife Sandy purchased the property for an undisclosed amount and closed this summer.

JQH Arena

Hammons pledged nearly $30 million toward the construction of JQH Arena, paying $1.9 million yearly. After his death, Hammons still owed $22 million in principal to Missouri State University. The school reached a settlement with JD Holdings last fall, returning the arena’s naming rights to MSU. JD Holdings will pay $8.4 million.

Hammons Field

The future of Hammons Field is still in the air, as the City of Springfield was in the mediation process with JD Holdings at the time of publication. The City owns most of the ground the stadium was developed on. The Hammons Trust is contractually obligated to repay the bonds issued to cover costs of developing the land.

Missouri Sports Hall of Fame

After some uncertainty, the future of the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame has been resolved. The building and land are now fully owned by the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame Foundation, and John Q. will continue to be listed as a founder of the organization.

Juanita K. Hammons Hall for the Performing Arts

While some buildings in the Hammons portfolio have transferred ownership to JD Holdings, Juanita K. Hammons Hall for the Performing Arts is not one of them. The venue is owned by Missouri State University, and Hammons’ pledged donation of $17.3 million was paid in full.

John’s Office

The epicenter of John Q.’s three-story office in the John Q. Hammons Office Building was the top floor. That space is being renovated by law firm Kutak Rock LLP. The law firm salvaged John Q.’s conference table and a few other items from his office they plan to incorporate into the new design.

“You could either file a lawsuit to enforce that gift agreement, or you could just take it on the chin and leave the name up there,” MSU General Counsel Rachael Dockery says. “We negotiated the strongest deal that we could.” On October 25, 2018, the university’s settlement with JD Holdings was approved. JD Holdings paid $1.8 million in May 2018, and will pay MSU $8.4 million between now and April 2022, and the naming rights for JQH were returned to the university. “While we’re very appreciative of the help of Mr. Hammons, this is not a situation either party wanted to find ourselves in,” Dockery says. “But naming rights allow the university to be whole financially.” For the time being, John Q.’s name remains on the facade of JQH Arena, but that will likely change when a new donor takes over naming rights.

As for Hammons Field, the City of Springfield objected to the Confirmation Order of the Hammons’ bankruptcy plan, and the case is currently going through a mediation process. While the city doesn’t claim ownership of the stadium, it does own most of the land beneath the stadium. When the stadium was being built, Springfield issued $6.1 million in bonds. Proceeds from the bonds were used to purchase and prepare the land under Hammons Field, and the Hammons Trust was contractually obligated to repay the bonds including the debt service. A portion of that debt is yet to be paid. But while the city is tied up in negotiations, the MSU Bears baseball program was able to negotiate a 12-year extension of its lease at the field. Highland Springs Country Club is now owned by JD Holdings, and the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame building and land are now fully owned by the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame Foundation.

What's in a Name?

After nearly three years of lawsuits, it’s hard to say how John Q.’s legacy has changed. But even if his name comes down from JQH Arena or Hammons Field, surely thatʼs not all it would take for John Q.ʼs legacy to fade. “Our whole community would be different if Hammons didn’t invest in us,” says Brent Dunn, vice-president for university advancement and executive director of the Missouri State University Foundation. By the time he died, John Q. had donated more than $30 million to Missouri State University. “Hammons was an early pioneer of private support that turned the entire campus around.”

John Q. donated an undisclosed amount to the creation of the Mercy Hospital Springfield Hammons Heart Institute, which opened in 1972. Around the same time, he purchased two rescue helicopters for the hospital to the tune of $1.2 million. He donated more than $300,000 to build the Fairview John Q. Hammons Community Center in his hometown. He developed Highland Springs Country Club and golf course. He’s credited as the founder of the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame, which has donated more than $15 million to area children through its annual golf tournament.

Is it possible that John Q. could be so involved in the growth of Springfield and not care about his legacy? Shantz Hart says yes. “He never talked about what he wanted to do with the business after he was gone,” she says. “He kind of thought he was going to live forever. But honestly, I don’t think he cared what happened. He was in the moment, and it was all about him.” For many, the height of the Hammons legacy will never connect with the end. Too much has changed, and too many things can’t be explained, or won’t be. “I wish people could see that he was a good guy,” Robbins says. “He really loved Springfield. I wish that could be the legacy, but whatever.”