Strategy

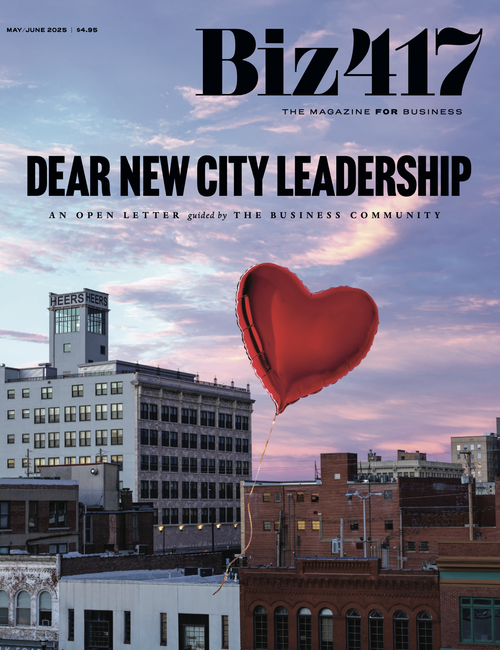

Hot Spots: Rising Developments in Downtown Springfield, Commercial Street and Galloway

How a group of determined developers are recreating three Springfield cityscapes.

By Vivian Wheeler | Illustrations by Alex Wolken

Jan 2018

Jump to A Section

Denver. Nashville. Portland. Austin. Springfield? It might seem like a stretch to include Springfield in a list of cities that are considered some of the hottest urban centers in the United States, but Lyle Foster, owner of Big Momma’s Coffee and Espresso Bar, likes to remind people that these cities weren’t always the destinations they are today. “Some of the best top cities 25 years ago were nothing,” he says. “[People] just got together and said, ‘We’re going to do something to this city to invest in our citizens or make this an attractive place.’” In Foster’s opinion, that’s currently happening in Springfield.

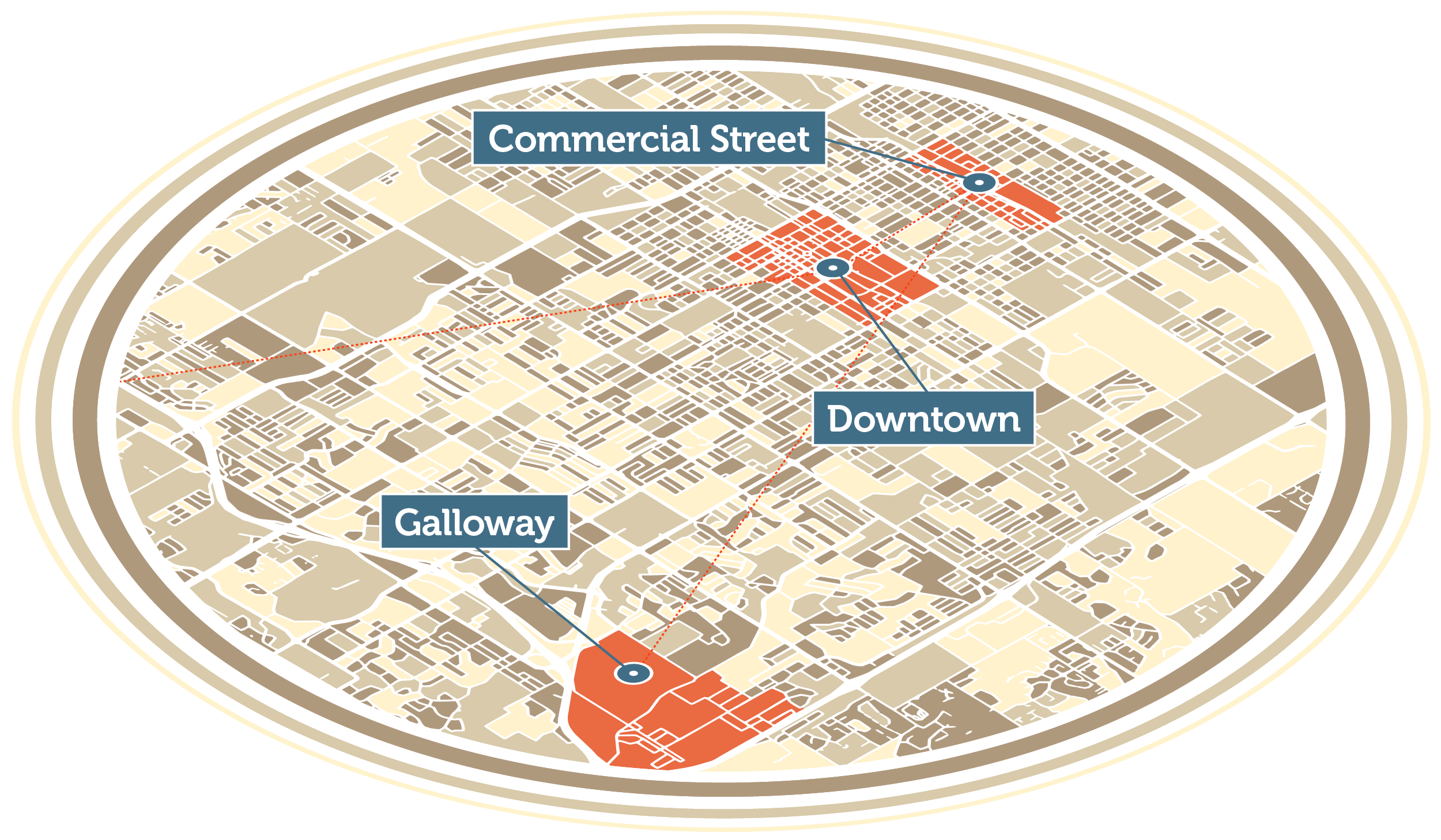

Led by a group of passionate people, development in Springfield is booming, especially downtown, on Commercial Street and in Galloway. Where parking lots and empty fields previously were, hotels and office spaces are popping up. Storefronts that sat vacant for 10, 15 and 20 years are once again bustling with business. And to the outside observer it might seem as if this growth has occurred on its own, but the reality tells a different story.

It’s a story of people driven to improve their community and transform the places they love. It’s a story of a city that has been aggressive about incentivizing economic growth. It’s a story of plans that were crafted decades ago slowly coming to fruition. And it’s a story still being written by developers who are capitalizing on 25 years worth of growth and planning and who are transforming downtown, Commercial Street and Galloway into hot spots.

Downtown Dreams

Rusty Worley, the executive director of It’s All Downtown, likes to joke that downtown Springfield’s urban renewal is a 25-year overnight success story. If you were to walk around downtown Springfield in the mid ’90s, you would have seen a vastly different scene from the one you see today. Gone would be the industrial glass sliding doors of Hotel Vandivort. You wouldn’t be able to check out a book at the Park Central library and tuck in to read it over a latte next door at The Coffee Ethic. Where Sky Eleven sits today sat the empty Woodruff Building—a once impressive structure that was, for a time, home to the Missouri Court of Appeals.

Like cities across the country, Springfield experienced considerable suburban flight throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, leaving the district a shell of its former self. Today, downtown is flourishing again. The influx of housing and businesses there stand as proof. In 1998, Worley estimates there were 25 lofts and 250 businesses downtown. Now, downtown has more than 800 lofts and 400 businesses. There are also 2,000-plus new student housing beds within the district. Most of these gains have occurred in renovated historic buildings, but downtown is starting to see new development as well. For example, a partnership among Missouri State University, The Vecino Group, the City of Springfield and the Springfield Business Development Corp., the economic arm of the Springfield Area Chamber of Commerce, is considering a multimillion-dollar expansion of IDEA Commons. All of this begs the question, what happened? How did downtown transform from a near-deserted district to the vibrant and growing community it’s become?

According to Worley, three major contributing factors jump-started downtown’s development. Created between 1996 and 2001, Vision 20/20 is a community-driven planning process that identified local issues of concern and created a comprehensive plan to address them. Around the same time the Vision 20/20 plan was created, Missouri State decided to expand into downtown. In doing its long-term planning, the university realized growing toward downtown was the only direction that made sense. Then, in 1998, the Missouri legislature enacted the Missouri Preservation Tax Credit Program, which acted as an incentive for developers to renovate historic buildings.

Bill Hart, the executive director of the Missouri Alliance for Historic Preservation, says the “program was designed to save important buildings and foster economic growth.” It gives developers who are renovating historic buildings a tax credit worth 25 percent of the qualified rehabilitation expenses. This is in addition to a similar federal tax credit worth 20 percent of the qualified rehabilitation expenses. However, unlike the federal tax credit, the state tax credit is transferable. Developers can sell the credits, which makes the state historic tax credit particularly enticing. Due to the state historic tax credits, Vision 20/20 and MSU’s expansion into downtown, the district started to see renewal, and developers began renovating some of the smaller buildings downtown. However, although these three factors supplied the kindling for a development boom, Dan Scott lit the match that ignited the blaze.

“I saw the potential and saw the possibilities with historic tax credits and decided to use that as a business model.”— Dan Scott, Owner of Jericho Development Co. LLC

Born and raised in Springfield, Dan Scott describes himself to other 417-landers as a York-Pipkin-Central kid. That is, he’s a westside boy who went to York Elementary School, Pipkin Middle School and Central High School. For college, Scott headed to Kansas University where he got a degree in architecture. He came back to Springfield to practice, and it was from the window of his office at Michael Sapp and Company PC, which was on Walnut Street where The Order is today, that he first realized what downtown could be. “I saw the potential and saw the possibilities with historic tax credits and decided to use that as a business model,” he says. He used the state historic tax credits to help fund the purchase of a couple of smaller buildings downtown, but when he set his eyes on 400 Place on Walnut Street, a project significantly larger in scale than his others, he knew he would need to be resourceful.

Scott had learned of a financial incentive called Chapter 99 tax abatement that developers in other Missouri cities were taking advantage of and decided to research it. The abatement is a statewide initiative that allows approved projects in blighted areas to be taxed at the predevelopment rate for 10 years. However, even though Chapter 99 is a statewide initiative, it’s administered at the city level, and no one in Springfield had applied for it when Scott started exploring the program.

“It was challenging to get into the program,” Scott says. When Scott was first applying for the abatement, there was a discrepancy between the way the city was potentially wanting to administer the abatement and the way the state statute was written. The city was exploring the idea of granting less than 100 percent tax abatement for 10 years. “I’m a researcher,” Scott says. “That’s part of what you do as an architect. I actually went through the process with the city where I kindly said, ‘That is not the way the state law is written. It’s actually 100 percent for 10 years.’” Scott ultimately received 100 percent abatement for 10 years, which made all the difference for his development plans. “I know I could not have done this project without those tax credits and could not have done it without pairing the historic tax credits and the Chapter 99 tax abatement,” he says. Today Scott’s office and the loft he shares with his wife are located in 400 Place, along with 14 lofts, Aviary Café, Ella Weiss Wedding Design and A Cricket in the House.

Since 2003, 28 other downtown redevelopment projects have received tax abatements, and you could argue that many, if not all, of these projects wouldn’t have happened had Dan Scott not made the Chapter 99 program workable for Springfield developers. Included in those projects are several businesses that have become staples of downtown, businesses such as Golden Girl Rum Club, Randy Bacon Photography, The Veridian, 5 Pound Apparel and more. Many of the projects were partially financed by historic tax credits and tax abatements. One firm that has been particularly successful in utilizing these incentives to redevelop several properties downtown is The Vecino Group.

Matthew Miller and Stacy Jurado-Miller founded The Vecino Group in 2011, but Miller’s foray into the development world began almost a decade earlier. After graduating from University of Missouri with a degree in Russian area studies and political science, Miller moved home to Springfield. The juxtaposition of Columbia and Springfield’s downtowns was striking to him. He says he saw a much more vibrant downtown in Columbia than in Springfield. Seeing downtown Springfield’s potential motivated Miller to help bring it back to life. He decided to open South Avenue Pizza Co., a restaurant and bar located where Finnegan’s Wake stands today, in 1992. Back then, “You could throw a rock and not worry about hitting anybody,” he says.

He eventually rented that building to a tenant, and it was then he realized he could make a living as a developer. He worked as a developer for the next nine years, but by the end of the recession, Miller started to burn out. He was ready to do something different. Jurado-Miller thought he was crazy. “At that point, he had gotten into affordable housing, and I said you can’t take a break,” she says. “It’s very hard to get into affordable housing.” Jurado-Miller knew how badly Springfield needed affordable housing and didn’t want her husband to lose momentum. Miller said the only way he would continue was for them to start a development company together. “I was fairly uninterested in development for development sake,” Jurado-Miller says. “But I am very interested in social justice issues and making a difference.” She agreed under the condition that they would use development as a tool to address broader social issues. Today they carry out that mission through a multitude of projects under The Vecino Group.

“You can find a Starbucks in Any City, USA, but Coffee Ethic and Mudhouse are ours.”— Matt Miller, CEO of The Vecino Group

For The Vecino Group to take on a project it must meet the team’s gut check. Essentially, does the project align with the company’s mission of housing for the greater good? “Every Vecino Group project has to address a broader need, set an example, give back to the community and inspire everybody working on it,” Jurado-Miller says. The Frisco Lofts are a prime example of that mission. Located on Jefferson Avenue between Olive and Water streets, The Frisco is a universally designed affordable housing community composed of 68 apartments. The complex has been full since it opened and often has a waiting list.

Today, The Vecino Group is currently working on projects in 10 states and has several projects throughout Springfield; however, it remains committed to downtown Springfield. Miller is drawn to the authenticity of downtown and wants to see Springfield’s urban core grow. “Downtown is what makes Springfield unique,” he says. “You can find a Starbucks in Any City, USA, but Coffee Ethic and Mudhouse are ours. Same for the restaurants, and theaters, and historic buildings downtown. There’s a collective city pride that’s on display every time you book a relative at the Hotel V instead of a chain hotel, or go have dinner at Bruno’s instead of the Olive Garden, or buy a movie ticket at the Moxie instead of going to a national franchise. You’re supporting local people, local history.”

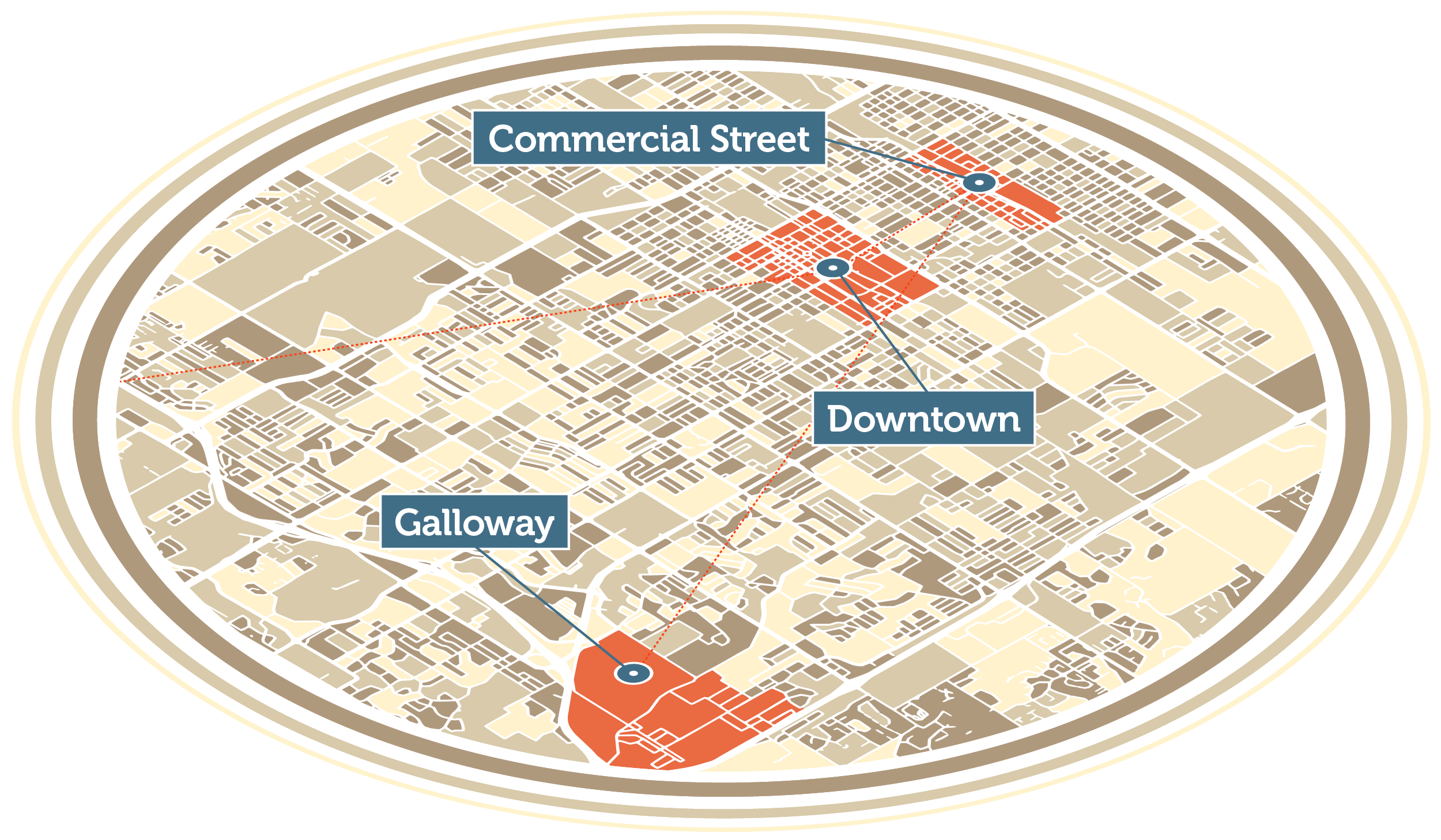

In addition to The Frisco, Vecino has redeveloped three historic buildings for student housing—The Sterling, The U and Sky Eleven—that all previously sat vacant, in some cases for decades. The company also recently completed a fourth student housing building, The Cresco Building, which is located across from The Frisco on Jefferson Avenue. Unlike other downtown Vecino projects, The Cresco is a new building built on a vacant parking lot. Tim Roth, The Vecino Group’s president of student housing, sees The Cresco as part of downtown’s next phase of development.

“All the major buildings have been brought back and historically renovated,” he says. “If you want economic vitality in the area, the very successful cities do infill. And successful infill is its own breed of design.” The Cresco will house 100 tenants on a half-acre lot. “It’s architecturally and engineeringly very challenging to do that,” Miller says. “We’re five, seven years away from maybe not needing parking lots with autonomous cars. What will happen to those parking lots? We’ll have additional opportunities for in infill. Successful cities figure that out.”

Like Roth and Miller, Worley also believes downtown development will transition from historic renovation to infill projects. “We’re getting to the point now where we really only have a handful of historic buildings left to renovate,” Worley says. “Most of the low-hanging fruit has been [redeveloped], and so you’re seeing a shift toward infill.” According to Worley, infill is important because it engages pedestrians and creates an experience while walking downtown. “The blocks that are from downtown to Hammons Field seem like an eternity,” he says. He would like to see some of those gaps filled in.

Another change Worley has witnessed is an increased demand for office space. “There was such a push on residential the past five years that now the pendulum is swinging more to the office side,” he says. Several companies have approached the Springfield Chamber and the city about relocating to downtown, but the types of spaces many companies are looking for are in short supply. “They’re looking for wide open spaces, 10,000 square feet or more, and we just don’t have many of those [buildings] that are ready for them to move into,” Worley says.

To address some of the demand for available office space, MSU, The Vecino Group, the City of Springfield and the Springfield Business Development Corp. have formed a public-private partnership to explore the possibility of expanding IDEA Commons. IDEA stands for Innovation, Design, Entrepreneurship and Art. The 88-acre innovation park includes the Jordan Valley Innovation Center, Brick City and The eFactory. It’s bordered by Chestnut Expressway, Water Street, Campbell Avenue and Washington Avenue. “This new development would include an expansion of JVIC, as well as the construction of a large new office building and several other amenities,” says Mat Burton, The Vecino Group’s lead developer on the project.

The proposed site of the expansion is a 2-acre lot of land sitting mainly on the southeast corner of Phelps Street and Boonville Avenue. Currently, Touche Night Club (the Vecino Group owns this building) and an MSU parking lot occupy the space. A welcome center, green spaces and community spaces are also being considered as part of the plan. The project has finished its due diligence phase, and the involved parties will spend the next several months assessing its feasibility. Part of that process includes evaluating the possibility of daylighting a portion of Jordan Creek in conjunction with the project.

Heating Up:

Highways 60 and 65 Interchange

Before the 2008 recession hit, big plans were in the works for three parcels of land owned by Larry Childress and his family. The almost 600 acres surround Highway 65 near Republic Road as well as Highway 60 north of Highland Springs. Today, improved economic conditions mean the bond sales required to fund an interchange connecting the area and Highway 65 are once again possible. “The interchange is the key to the puzzle,” says Dave Murray, president of R.B. Murray Co. “When it goes, then the rest of the development can take place.”

Chestnut Expressway and Highway 65

Be on the lookout for a new Menards opening late this summer. The store is replacing the old Hickory Hills school on North Eastgate Avenue and, according to a company representative, will have “the latest, greatest home improvement products to include a full-service lumberyard with a covered warehouse, beautiful garden center, pet and wildlife department, appliances, a line of convenience groceries, many great departments and displays.”

Currently, Jordan Creek runs under downtown Springfield, and a variety of community leaders over the past decade have talked of bringing the creek above ground. Worley, for one, would like to see the project come to fruition. “What we’ve seen by visiting other cities is that people are drawn to water, whether it is on a riverfront, a lakefront or ocean,” he says. “We don’t have any of those here in Springfield. The closest thing we have is Jordan Creek.” In addition to drawing more people downtown, daylighting Jordan Creek could help manage flood control, beautify downtown and spur economic growth.

The potential for economic growth has Scott excited about the prospect, too. Scott feels the next big boom in downtown development won’t happen without a large city-led project like daylighting Jordan Creek. Scott points to Oklahoma City as an example of the effect it could have. Oklahoma City made the investment in a downtown waterway 18 years ago on what was mostly vacant land. Consequently, the area saw a burst of new development, including the addition of a Bass Pro Shops near the waterway.

Although many people in Springfield would like to see Jordan Creek brought above ground, the project currently lacks funding, and there is no immediate solution in sight. According to Sarah Kerner, economic director for the City of Springfield, daylighting Jordan Creek could potentially be funded by the property level tax that voters renewed this past November. However, she says it might be a tough sell to spend money on a project like daylighting Jordan Creek when there are significant public safety needs, such as the two new fire stations for the north side. “It’s going to be a balancing act going forward,” she says.

What’s Next for Downtown?

Find out what projects are in the works in downtown Springfield

Moxy Hotel

Tim O’Reilly, founder and CEO of O’Reilly Hospitality Management, is redeveloping 430 South Ave. into a millennial-focused hotel. The project is reported to be a franchise of Marriott International’s Moxy hotel and will have 98 rooms, according to the Springfield News-Leader.

214 McDaniel St.

Darren Smith, owner of Veridian Events, is developing a project across from The Veridian on McDaniel Street. The four-story building will hold a basement speakeasy bar, a banquet facility, five Airbnb rooms and a rooftop bar and pool area. The project is set to begin construction in January with plans to be completed in 9 months.

The Newberry Building

Smith also owns the Newberry Building, a 50,000-square-foot property on the southwest corner of Park Central Square. Smith says the project is still in the architectural planning phase and hasn’t released plans for the building.

The Foster Building

Sam Chimento, a St. Louis developer, is in the process of redeveloping and expanding the Foster Building, which is across from the YMCA on Jefferson Avenue. The property is L-shaped with frontage on Walnut Street. Chimento plans to develop the property as a 212,000-square-foot student housing complex with 344 beds, a zero-entry pool on the second story, yoga studio and club house. Construction is set to begin this spring and be completed by summer 2019.

Hotel Vandivort Expansion

Karen, John and Billy McQueary are exploring the idea of expanding Hotel Vandivort due to higher-than-expected demand. One option being considered is building an extension of the hotel where the parking lot is.

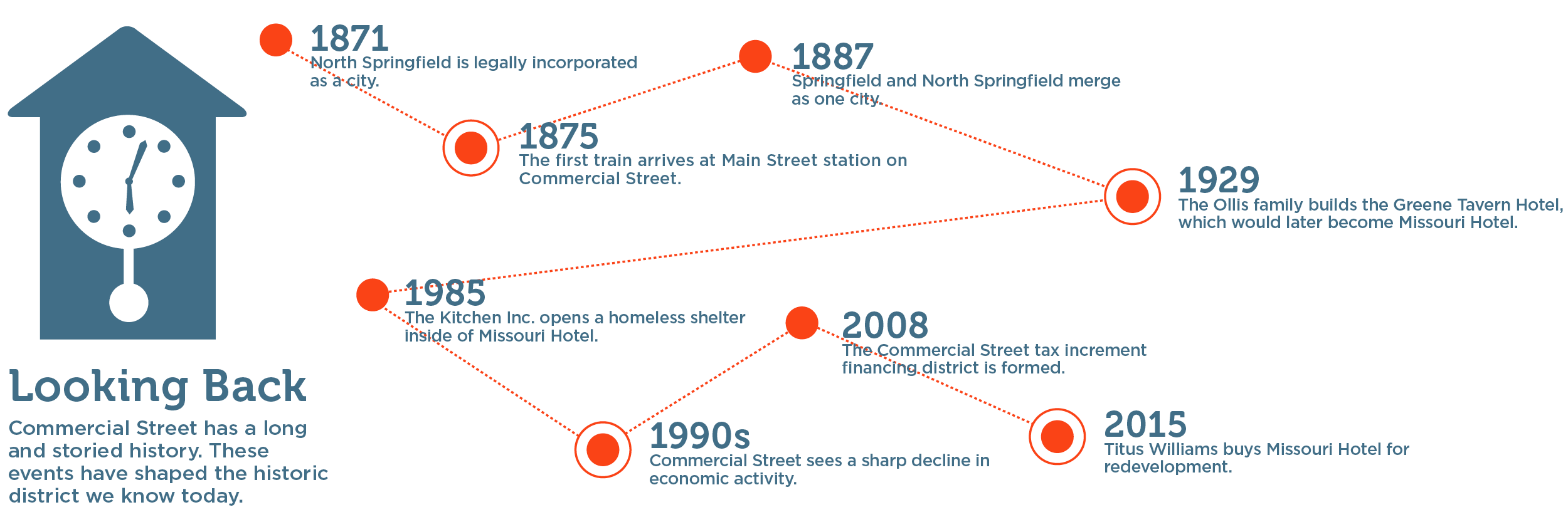

Rewriting Commercial Street's History

Just 2 miles north of downtown, Commercial Street has been undergoing its own economic transformation over the past 25 years. Like downtown, this growth did not happen by accident but took concerted effort by passionate individuals. And no one has been more passionate about C-Street than Mary Collette. Collette’s father was in the Air Force and throughout her childhood, they traveled extensively. “We lived in England, and we lived in Germany and traveled throughout Europe, and I had never found a place in Springfield that reminded me of that until I came up here,” she says, referring to C-Street. “And I just fell in love with it.” In 1980, Collette bought the building on the southeast corner of Boonville Avenue and Commercial Street. A graphic designer, she started living and working out of the building. “I was able to purchase that building for the same amount I was paying in rent on a little house,” she says. Over the years, Collette has continued to invest in the area.

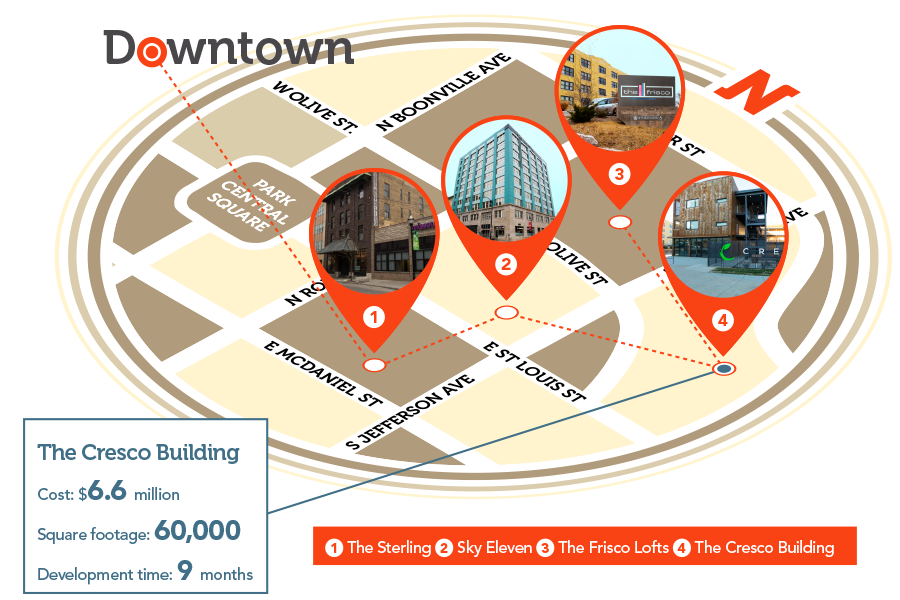

Today she and her husband own three buildings on Commercial—including the Historic Firehouse No. 2, which Collette purchased when a prospective buyer wanted to put a parking lot on part of the property—and recently sold two others. Along with owning a business on C-Street, Collette is the president of the Commercial Club, a community organization founded in 1928 that is dedicated to advancing the interests of the district. It was the Commercial Club that first recommended that the city purchase Frisco Lane, a strip of 67,000 square feet extending along the back of the businesses lining the north side of Commercial. That was 25 years ago, and it was just this past August that the city purchased the land from BNSF Railway.

At a price tag of $999,105, those 67,000 square feet did not come cheap, but for the merchants of C-Street, it was needed. Before the city acquired the land, the business owners on the north side of Commercial technically did not have access to the back entrances of their buildings; BNSF Railway owned the land flush to the backs of the buildings. This meant placing dumpsters and parking there was illegal and that back entrances could not be used as public entrances. The building west of Historic Firehouse No. 2 was denied a grant from the Department of Housing and Urban Development because it did not have access to a back entrance. That building stands vacant today. In addition to granting business owners access to the backs of their buildings, Frisco Lane allows for expanded parking, which has increasingly been an issue as the district becomes more popular.

And although $999,105 sounds like a lot of money for that much space, much of that cost was offset by a $707,850 credit BNSF issued the city two years ago in exchange for 2.6 acres of land the railroad bought. Another $268,151 was funded by the Commercial Street tax increment financing district (TIF), which was created in 2008. When a TIF is formed, the tax level within the district is locked in for a prescribed amount of time, which is 23 years for C-Street’s TIF. Any increase in taxes above that base rate is captured by the TIF and can be used for public improvements. To date, C-Street’s TIF has captured $583,977.

Lyle Foster remembers going to the planning meetings when the Commercial Street TIF was first proposed. Foster was living in Chicago when he first discovered Springfield and Commercial Street. His daughter was playing basketball for a college in Austin, Texas, and Foster came down for a weekend to watch a game against Drury University. While here, he decided to check out what Springfield had to offer. “I describe myself as an urbanologist, which means I love everything about cities,” he says. “I decided to explore Springfield, and in one of those more fortuitous things, I discovered the historic district.”

At the time, Foster had no intention of moving to Springfield, but he was interested in redeveloping a property into lofts. “I had studied a number of cities that I thought were coming into their season,” he says. “But my thing is, when cities get into their season, you can’t afford them.” Foster saw C-Street’s potential and bought the building where Big Momma’s is today. He redeveloped it, which was a big undertaking as the building lacked a back wall on all three stories. “It’s really a labor of love,” he says.

During the renovation, Foster was driving back and forth from Chicago to oversee the progress. When the renovation was complete, he continued to split his time between the two cities, but as the storefront of his building sat empty, he started to feel guilty. He saw the other empty storefronts up and down Commercial Street and felt like he wasn’t doing enough to improve the area. “One morning I just woke up with the idea of, well, I love coffee shops,” he says. “I love what they can do as community spaces and building community, and maybe I’ll try to do that.” However, Foster knew opening a coffee shop would mean moving to Springfield.

Big Momma’s opened in 2007. Even then, Foster still didn’t see himself living in Springfield long-term, but he says during the following years, he fell in love with C-Street, Big Momma’s and slowly the people. In 2009, he bought a second building, where wine bar Q Enoteca is located. Since 2004, Foster has watched the area transform into a vibrant district with a growing business community. Today Commercial Street is home to a slew of businesses including White River Brewing Co., Askinosie Chocolate, Departika, The Vecino Group and many more.

While Foster acknowledges C-Street’s growth, he thinks there are still a few linchpin development projects that need to be completed. One of those projects is the Missouri Hotel, which is currently being renovated by Titus Williams, owner and chief operating officer of Burning Tree Consulting LLC. Williams already had his eye on Commercial Street when he learned the Missouri Hotel was becoming available for purchase. The Kitchen Inc., a local nonprofit organization, ran a homeless shelter out of the building until 2014 when it put the building on the market and shifted its focus to providing permanent housing.

“We are social animals. We need to be around other people. We need to build relationships.”— Titus Williams, Owner and COO of Burning Tree Consulting LLC

Williams originally planned to redevelop the Missouri Hotel with partner Matt Max Miller, and they purchased the property together. However, after a family medical crisis caused Miller to step away from the project, Williams made plans to buy out Miller’s portion of the building. Along with the Missouri Hotel, Williams is also redeveloping 12 other buildings nearby—with possibly more to come. Williams is still in the process of acquiring property for redevelopment. Depending on how many properties he is able to acquire, the project could range from $20 million to $50 million. Williams plans to create a destination center where people come for an experience. The project is anchored by a boutique hotel with connected multifamily housing, in which residents could take advantage of the hotel’s amenities, such as room service and dry cleaning. Also planned are artisanal shops and other unique retail options, office space and a distillery. Williams sees C-Street evolving into a travel destination where people would come and spend a weekend exploring the district, and he hopes the Missouri Hotel project will push that evolution along.

The idea behind the project is shaped by what Williams sees as a cultural shift towards authentic, community-focused housing and shopping experiences. He thinks this is especially true of the millennial generation, who are changing the way we shop. “When you go to Walmart, memories aren’t really made,” he says. “But when you go to Askinosie for the first time, you have a memory. Something brand new is created at that point in time.” Millennials are also bucking at more recent housing conventions. “Going out into the suburbs, that’s all fine and good,” he says. “But I believe we are the only society where we have these big beautiful houses, and you drive into your garage, and you lock yourself away from anyone else. We are social animals. We need to be around other people. We need to build relationships. And the way our society has been shifting in the last 50 years is to the suburbs. We’re becoming isolated more and more and more.” Essentially, the attitude is shifting from keeping up with the Joneses to becoming friends with the Joneses.

Although Williams has big plans for the Missouri Hotel and the surrounding properties, the size of the project depends on the availability of certain tax credits. Like many of the other C-Street developers, Williams plans on using federal and state historic tax credits to help fund the project. Williams also hopes the Missouri Hotel project qualifies for a New Market Tax Credit, a federal tax credit for investors in low-income communities, but the credit has a cumbersome application and strict qualifying standards. In addition to being uncertain about qualifying for a New Market Tax Credit, Williams faces uncertainty surrounding historic tax credits. There is concern among the local development community that Gov. Eric Greitens might abolish state historic tax credits, as he’s already voted to cut state funding for affordable housing tax credits. In November, Greitens voted as part of the Missouri Housing Development Commission to not allocate $140 million toward the Missouri Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program. That measure passed 6 to 2.

If Williams is unable to secure historic tax credits, he would have to significantly scale down the size of the project. However, if all goes according to plan, he will submit his application for tax credits this May, and he hopes to complete the project over the next two years. You won’t have to wait that long to see new spots open up throughout the historic district, though. In the next few months, Uriels’ Unusual Bookstore and Van Gogh’s Eeterie are scheduled to open. C-Street’s retail space is becoming a hot commodity. Eight businesses opened on Commercial Street in 2017, and it looks as if growth won’t be slowing down anytime soon. “I’ve seen first floor retail space in some cases triple [in rent] from where they were six, seven or eight years ago,” Foster says. “But here’s the second piece of it: Not only did they triple, but people were actually bidding for the spaces.”

Starting Fresh in Galloway

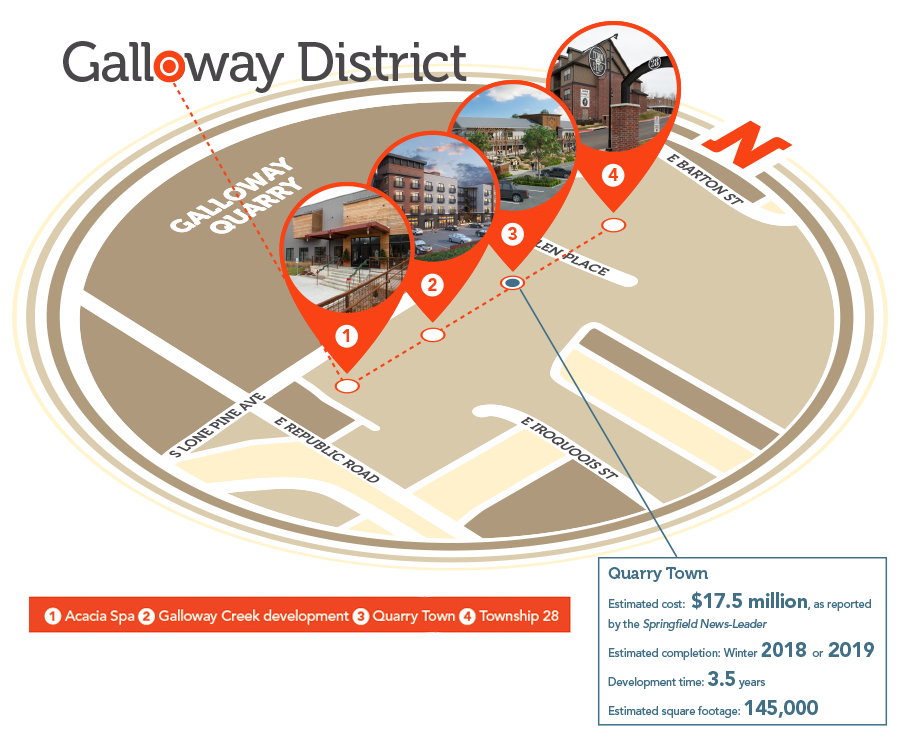

Running along Lone Pine Avenue south of Battlefield Road, the Galloway neighborhood has long been a popular destination for those looking to hit the Galloway Creek Greenway, enjoy a picnic at Sequiota Park or patronize one of its eclectic businesses—places like Creekside Pub, Firehouse Pottery and Sequiota Bike Shop. Still, most of the land in the Galloway neighborhood sat undeveloped until a couple of years ago. Since 2015, the neighborhood has seen new developments of a 10,000-square-foot luxury spa and a 138-unit apartment complex, and there are two more large-scale projects in the works.

To understand why Galloway has seen so much growth so quickly, look no further than Sam M. Coryell. Coryell is the president of TLC Properties, the property management company his parents started in 1988. Coryell grew up in Springfield and always enjoyed the Galloway area. “Back in high school, we’d go down there and go to the park and go in that cave and hang out,” he says. “I’ve just always had a place in my heart for it.”

“Part of it was just a desire to see that area redeveloped, and [I] knew somebody had to do it. Somebody had to take a chance.”— Sam M. Coryell, President of TLC Properties

As an adult, Coryell and his wife often take their kids to Sequiota Park and walk along the trail. It was on one of these walks that Coryell first thought Galloway had development potential. He was walking along the trail when he spotted a white building with a chain-link fence around the property. He says it looked awful but thought it would be a nice place for apartments. “Part of it was instinctual,” he says of his decision to purchase the property in 2008. “Part of it was just a desire to see that area redeveloped, and [I] knew somebody had to do it. Somebody had to take a chance.” Then the recession hit.

The property sat idle until 2013 when Coryell picked the project back up again. “I started getting prices to build, and it was just too expensive because of the terrain up there,” he says. “There’s a lot of rock.” Coryell and his attorney met with the city to see if they could get the property blighted in hopes of qualifying for the Chapter 99 tax abatement, which would help make the project financially feasible. As Sarah Kerner explains, there are several reasons a property can be blighted by the city: if the property has structures in very poor condition, if there is criminal activity on the property, if the property has infrastructure problems or if the property is not properly platted. “You don’t have to see all of those things, [but] you have to see a predominance of those things,” she says. “Blight is kind of like obscenity; you know it when you see it.”

When Coryell met with Mary Lilly Smith, planning and development director for the City for Springfield, Smith explained Coryell’s project would have a better chance of being blighted if Coryell applied for blight for the whole area as opposed to just his property. She said the city was looking at blighting the area, but that they didn’t have the resources at the moment. To the outside observer, it might not look like Galloway would be eligible for a blight designation, but the platting was prohibitively antiquated. “Galloway was formerly a village, a separate village from Springfield,” Kerner says. “If you looked at the lots’ lines on a map, it’s crazy.”

Coryell was undeterred when he learned the city didn’t have the funds to blight Galloway. “I said, ‘Well, what if I paid for it?’” he says. “Would the city support it? And she said absolutely.” Coryell spent $50,000 in an effort to blight Galloway without a guarantee it would happen. Even if the city recommends a blight designation, City Council has the final say. In the end, the Council approved the blight.

Coryell broke ground on his apartment community, Township 28, in February of 2014. The project was completed in December 2016. According to Coryell, the complex stays above a 95 percent occupancy rate. “At the time, I was pricing it really high for Springfield,” he says. “That was scary because most of my network is between 75 and 80 cents a square foot per month. [Township] was at $1.15. That means a thousand-square-foot apartment is going to be over $1,000 a month.” Coryell seems to have set the tone in regard to pricing for future residential developments in Galloway. Two more residential projects are in the works, both of which plan to offer high-end apartments.

Once Galloway received the blight designation, other development projects soon followed. Brent Brown, co-founder and partner of Entrust Property Solutions, always thought Galloway had a lot of potential for development. “I’m one of those guys who stood on the sideline and looked at it and always thought it would be great,” he says. Brown started looking for property to buy once Galloway was blighted, but there was none available. He approached the Jalili family—owners of Flame, Touch and Black Sheep—about buying a tract of land they owned, but they didn’t want to sell. The Jalilis had plans to build a restaurant there. After talking, the three decided to partner on a mixed-use project.

The Galloway Creek development will feature 12,000 feet of commercial space and 66 luxury-style lofts, a combination of 30 studios and 36 one-bedroom units. As part of the commercial space, the Jalili family is opening Chops, a new boutique steakhouse. Also planning to open locations there are a coffee shop, Pure Hot Yoga and Culture Flock, a clothing business co-owned by Brown, his sister, Summer Trottier, and her wife, Brittany Bilyeu. The project is set to be completed by September.

Walk just 269 feet to the south of the Galloway Creek development and you run into the future site of Quarry Town, a mixed-use development project owned by Matt O’Reilly, CEO of Green Circle Projects. An outdoor enthusiast and longtime fan of Galloway, O’Reilly wanted to ensure the land was redeveloped properly. “I’ve always been attracted to that corridor,” O’Reilly says. “It’s a really unique part of Springfield. Knowing that it was going to be developed, I wanted to help shape it. I wanted to get in there and try to do it right.”

O’Reilly’s project has three components that will roll out in two phases. The first phase includes 20,000 square feet of combined commercial, restaurant and retail space and a 101-unit apartment complex. O’Reilly’s plan for the apartment complex includes a pool, individual garages and quality finishes. “It’s going to have a lot of attitude for a market-rate apartment complex,” he says.

As for the second phase of Quarry Town, O’Reilly plans to build a pocket neighborhood of high-end, small town homes in the woods on a hillside behind the apartment complex. “I’ve always had a passion to develop a house that can go anywhere, and that basically means it would need to be on stilts,” he says. “In the Ozarks, there’s all kind of really great land that’s rocky and in the woods.” The town houses are still in the product development phase, and O’Reilly plans to roll them out after the first phase is completed, which is scheduled to be finished this fall.

In addition to the development of Quarry Town, Township 28 and Galloway Creek, Acacia Spa relocated to a 10,000-square-foot building in Galloway in June 2016, and, as of press time, 4 by 4 Brewing Co. is set to open very soon. The influx of new development has raised concerns over the state of the existing infrastructure in Galloway. The district has flooding issues. O’Reilly has been working with the city to pass an improvement plan that would allow them to expand the size of a culvert, which runs underneath a railroad track. “Getting permission to do anything under a rail is like an act of God,” O’Reilly says. His team has removed debris from the creek that was prohibiting water flow and causing additional flooding. There has also been some talk among the Galloway developers of establishing a community improvement district with the idea that funds collected could help correct the infrastructure problems. In addition to addressing those issues, O’Reilly is concentrating on environmental concerns within the district. He created a partnership between the Missouri Stream Team, Watershed Committee and the City of Springfield to monitor Galloway Creek’s water quality. The team has established a set of water quality metrics they can monitor over time as the corridor continues to develop. “Usually an increase in quantity is a decrease in quality,” O’Reilly says. “The extra flow causes erosion and all kinds of other problems.”

The full environmental impact of Galloway’s development is yet to be seen, as there is still land in the Galloway district that could be developed. Most of that land is owned by O’Reilly, who won’t disclose specifics of his plans for those plots but says the overarching principle is to preserve what people love about Galloway while preventing the potential pitfalls of development.

O’Reilly, Brown and Coryell say that without Chapter 99 tax abatements their developments in Galloway would not have happened, but the tax incentive is not without its critics. The way the law is currently written, if a property is blighted and the proposed project complies with the redevelopment plan, the abatement is granted. Currently, a project does not have to prove the development needs the abatement to be financially viable. “There’s just this general thought in the community, especially around Council, that’s kind of like, ‘Do they really need this abatement?’” Kerner says. “Under our current program, we don’t have a way of testing it.”

Heating Up:

Finley River

According to Bob Noble, president of Noble Communications, the city of Ozark has a vision to turn the area surrounding the Finley River in Ozark into a destination location. Potential attractions could include the Ozark Mill, which Johnny Morris owns; Rivercliff House, a property Noble plans to turn into a corporate retreat; the Smallin Civil War Cave and more.

Kearney Street

In an effort to rehabilitate the street that was once declared “hideous” by the author David Sedaris, the city has been working on creating a redevelopment district that runs along Kearney Street between North Kansas Expressway and North Glenstone Avenue. Although initial plans have been crafted, the process is on hold until the Chapter 99 tax abatement administrative hold has ended.

In October, City Council placed a temporary hold on new redevelopment plans for blighted areas to allow the city to craft new guidelines for Chapter 99 tax abatement. These new guidelines, called a workable program, will include a “but-for” test, which means that but-for an abatement, a project could not happen. “It’s only fair,” Kerner says. “You shouldn’t get an incentive just because you checked a couple of boxes. You should actually need it. This is essentially forgone tax money.”

Another proposed provision of the workable program would reduce the guaranteed tax abatement rate from 100 percent to 50 percent. Developers could then increase their percentage of tax abatement by showing that their projects go above and beyond remediating blight. The program would work like a scorecard, with developers earning points for additional benefits included in the project. Benefits could include features like sustainable design, developing in a financially distressed area or high-quality landscaping. Each point earned by a project would equal one extra percentage point of abatement. The city is still working out the fine print of the workable program, and no new redevelopment plans can be submitted until the program has been passed.

“You shouldn't get an incentive just because you checked a couple of boxes.”— Sarah Kerner, Economic Director for the City of Springfield

Along with changing the way the Chapter 99 tax abatement program works, the city is working to simplify the development permitting process. Deputy City Manager Tim Smith is spearheading the effort and spent a year working with city employees, the development community and People Centric Consulting Group to create a predevelopment meeting that would streamline the process. According to Smith, the city has faced criticism over the years about the slow and unpredictable nature of the process. The predevelopment meetings, the first of which happened last October, are designed to get all the city departments that touch the permitting process in one room to anticipate and troubleshoot any potential snags a project might encounter. Participation in the predevelopment meetings is optional, but Smith says so far, the response from the development community has been positive. Coming up with creative ways to encourage development is becoming increasingly important as the development climate is becoming increasingly precarious.

With the Chapter 99 tax abatement program in limbo, historic and affordable housing tax credits on the chopping block and no secured funding for daylighting Jordan Creek, the future of development in Springfield is uncertain. Has the recent growth created enough excitement and energy that development will continue to accelerate? Or will development plateau? Jurado-Miller, for one, is concerned about what eliminating the tax credits means for future development. “Every development of ours in downtown Springfield took federal, state and city incentives to become a reality,” she says. “So, when you eliminate some of those things, you are eliminating the best developments in Springfield, [in] Missouri and across the country. I think the only thing that is certain is developers are, by their nature, persistent.”